Philosophy Series Contents (to be updated with each new installment)

Philosophy Series 1 – Prelude to the Philosophy Series

Philosophy Series 2 – Introduction

Philosophy Series 3 – Appendix A, Part 1

Philosophy Series 4 – The Pre-Socratics – Hesiod

Philosophy Series 5 – A Detour of Time

Philosophy Series 6 – The Origin

Philosophy Series 7 – Eros

Philosophy Series 8 – Thales

Philosophy Series 9 – An Interlude to Anaximander

Philosophy Series 10 – On the Way to Anaximander: Language and Proximity

Philosophy Series 11 – Aristotle and Modernity: The Eternal and Science

Philosophy Series 12 – Levinas and the Problem of Metaphysics

Philosophy Series 13 – On Origin

Philosophy Series 14 – George Orwell and Emmanuel Levinas Introspective: Socialism and the Other

————————————————

Appendix A

(Note: This appendix was originally planned to be released in whole near the beginning of the first chapter. However, its size has grown too large to publish as one post. Additionally, it would probably be better to release sections of the appendix which correspond to subject matter in the chapter releases. Therefore, I have decided to release it piecemeal.)

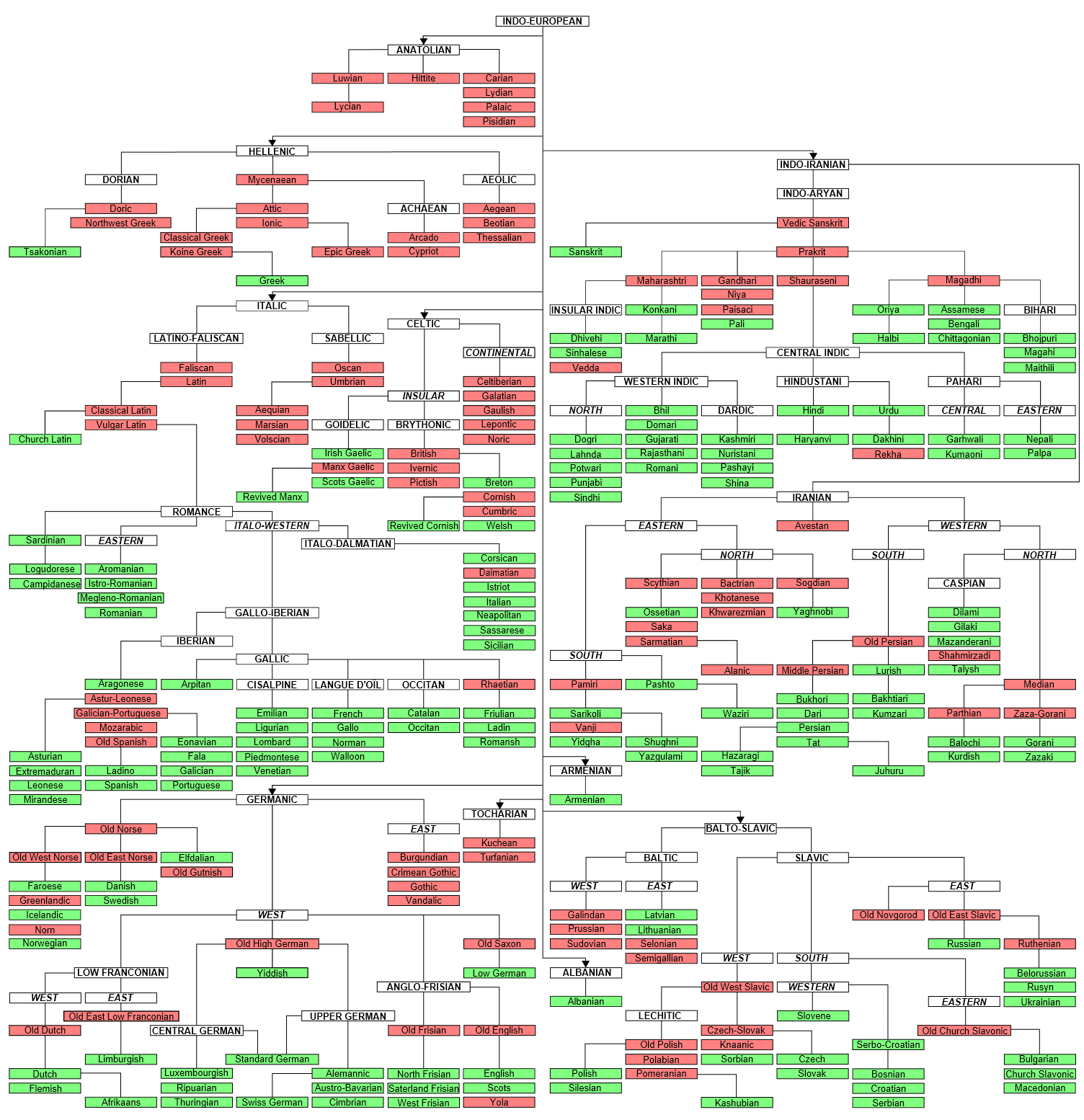

Before the Greeks

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is a common language that many scholars believe was spoken long before classical Greece, as early as 3,700 BC and possibly into upper paleolithic before the 10th century BC. The theory of PIE has been developed over several centuries. PIE is still a theory because it preceded writing. PIE was only oral. It was developed by a linguistic archeology (archē and logos) that links common grammatical and roots or stems of words in various ancient languages. Here is a chart of how PIE may have split into various languages.

Greek Philosophy and Periods

To start, these are generally accepted Greek histories, dialects and some pertinent facts:

| Proto-Greek (c. 3000–1600 BC)

Ancient Greek and Vedic Sanskrit suggest that both Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian were quite similar to later Proto-Indo-European (somewhere in the late 4th millennium BC)

|

| Mycenaean (c. 1600–1100 BC)

Bronze age, Linear B, oral

|

| Greek Dark Age (c. 1100-800 BC)

Dorian invasion to the first signs of the Greek

|

| Ancient Greek (c. 800–330 BC) Dialects: Aeolic, Arcadocypriot, Attic–Ionic, Doric, Locrian, Pamphylian, Homeric Greek, Macedonian

|

| Koine Greek (c. 330 BC–330)

Hellenistic period, the common dialect, translations include the Christian New Testament and the Septuagint |

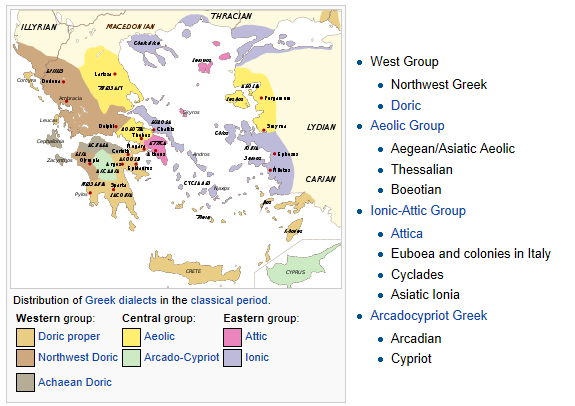

Homeric Greek (or epic or poetic Greek) is an early East Greek blending of Ionic and Aeolic features. Aeolic includes the Lesbian and the Thessalian and the Boeotian dialects.1 Ionic may go back to the 11th century BC while Aeolic may go back to the 14th century BC. Homeric Ionic is called ‘Old Ionic’. The later Ionic called ‘New Ionic’ used by many ancient philosophers started around the 6th century BC. Many of the well known ancient philosophers wrote in the Attic-Ionic dialect. The Aeolic dialect was more archaic than Attic-Ionic, Doric, Northwestern and Arcadocypriot. It was considered more barbaric than the Attic-Ionic used during the time of Plato.2

Around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration in Mesopotamia outgrew human memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form.

By definition, the modern practice of history begins with written records; evidence of human culture without writing is the realm of prehistory.3

Homer and his Iliad and Odyssey are said to be part of an oral tradition. Since the Iliad and Odyssey were written down, it should be emphasized that they came out of the earlier oral period. It is thought that the epics we know today are the result of generations of storytellers (a technical term for them is rhapsodes) passing on the material until finally, somehow, someone wrote it.

An epithet (Greek — επιθετον and Latin — epitheton; literally meaning ‘imposed’) is a descriptive word or phrase that has become a fixed formula.4

Homer and Hesiod wrote in a form of poetry that was rhythmic and rhymed. It was probably sung for many centuries orally before it was finally written down. The written form of Homer and Hesiod, when the poets were finally transcribed probably goes back to 750 to 600 BC.5 It could be thought as the earliest form of what we might call “rap” today. The oral tradition of their poetry may go back to 1400 BC or even earlier.6

Philosophers that wrote in Old Ionic were Heraclitus, Hecataeus and logographers, Herodotus, Democritus, and Hippocrates.

Attic Orators, Plato, Xenophon and Aristotle wrote in Attic proper, Thucydides in Old Attic, the dramatists in an artificial poetic language[8] while the Attic Comedy contains several vernacular elements.

Geography and Greek Dialects7

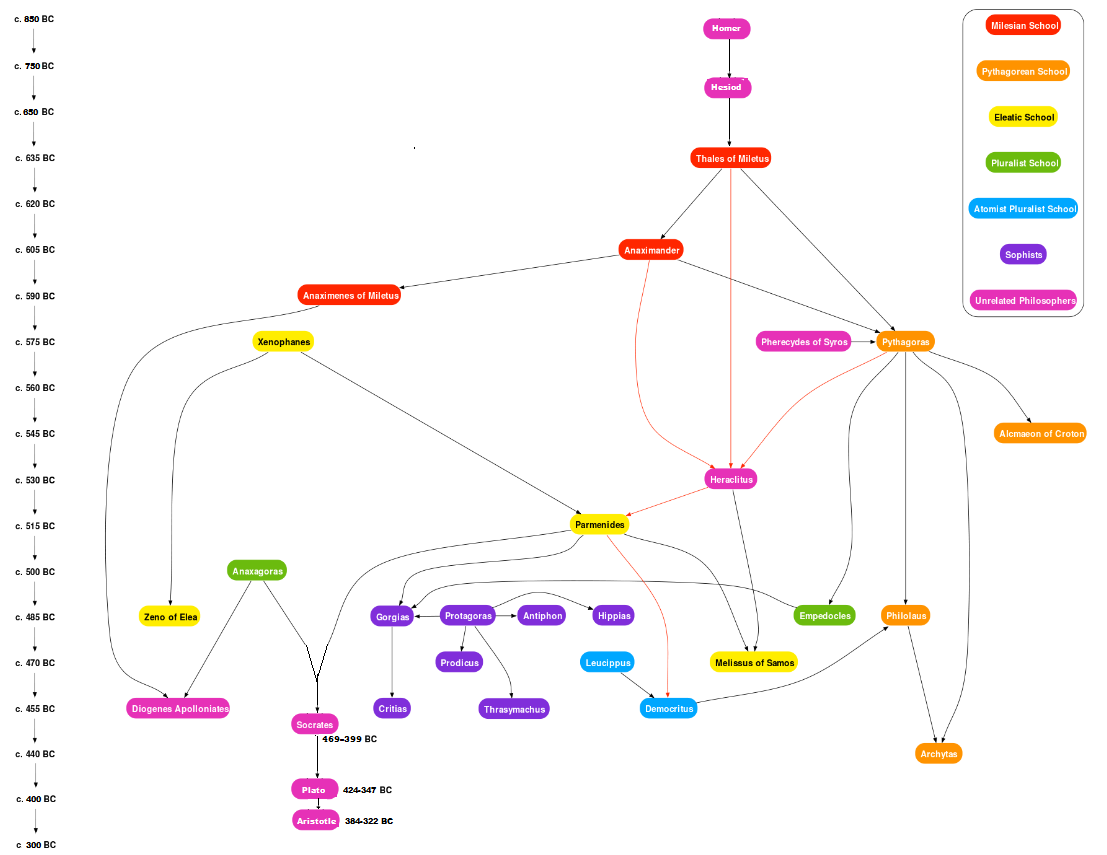

Greek Schools

Ancient Greek philosophy is widely varied and rich. It is problematic to accurately schematize the philosophers. There are cases where traditional scholarship includes a thinker in a school not because the philosophers had an abundance of ideas in common but because one was thought to be a student or influenced by the other. With this in mind, we can sketch out six main schools of ancient Greek philosophy: Milesian, Pythagorean, Eleatic, Pluralist, Atomist and Sophists and unaffiliated philosophers. These schools have some common threads in that they are all focused on what ‘is’ or what shows itself in nature or phusis. Heidegger maintains that phusis, the word we know as physics, was the original word the Greeks had for being.

In the age of the first and definitive unfolding of Western philosophy among the Greeks, when questioning about beings as such and as a whole received its true inception, beings were called phusis. This fundamental Greek word for beings is usually translated “nature.” We use the Latin translation natura which really means “to be born,” “birth.” But with this Latin translation, the originary content of the Greek word phusis is already thrust aside, the authentic philosophical naming force of the Greek word is destroyed… Now, what does the word phusis say? It says what emerges from itself (for example, the emergence, the blossoming, of a rose), the unfolding that opens itself up, the coming-into-appearance in such unfolding and holding itself and persisting in appearance–in short, the emerging-abiding sway… phuein [the noun form of phusis] means to grow, to make grow (Introduction to Metaphysics, 14-15).

It is interesting to note one of the Indo-European root words for being is associated with the etymological roots of the Greek word phusis:

Another Indo-European root is bhú or bheu. Out of this we get “be,” “been,” bin, and bist. Significantly, from this root also comes the Greek phuein (to grow, emerge) and phusis. The Greek term phainesthai is also derived from this root. This word means “show” or “display,” and “phenomenon” is derived from it.8

Julius Pokorny, a linguist, also believes that the Sanskrit word Brahman, a very important concept in Buddhism and Hinduism, also comes from the same Indo-European root (also see the root *bʰuH in the section, Being and “to be”, below).9

Early Greek philosophy was intensely focused on being and phusis with questions such as: is being and existence real or illusion, one or many, idea or substance (such as water or fire)? Many scholars think that the shift from Greek mythos to phusis is the beginning of philosophy. This shift becomes apparent with the Milesians and continues through the various Greek schools. Their concerns were focused on what shows itself in phenomena (from phainesthai). They were fully aware that what shows itself may not always be immediately apparent at all. It could also show itself as semblance, as what it is not (i.e., as Gods or already understood as a multiplicity of lifeless and separate things). They were also keenly aware that what shows itself is not simply a thing before us that we passively see. When we see phenomenon, phusis must retreat in the act of our seeing and observing. Phusis has a way of withdrawing in order to make it possible to see (long before Schrödinger’s cat10). Perception, thought and speech, the logos, requires a kind of dynamic privation, a retreat into the background of we might think as ‘context’ but the Greeks would think AS phusis. This is important as the difference demarcated by ‘context’ and phusis shows a historical difference which cannot easily be overcome. When thinking about these philosophers and schools modern reductions show early Greek thought as ‘primitive’ and ‘archaic’. However, these convenient castings obscure more than they reveal. They vastly restrict and miss important possibilities forged and virtually lost by these early thinkers. For some of these schools, a certain kind of preoccupation with all that ‘is’ leads to theories of all one or monism. For others, the problem this way of thinking leads to is, how can multiplicity and change be thought from the standpoint of sameness? Each of the schools had different ways of addressing these questions. What follows is a high level summary of these schools of thought.

This is a rough timeline and various schools of Greek philosophy.11

Milesian

Miletus was a city in Ionia, on the west coast of what is now Turkey. It was a trade route to the older cultures of Babylon, Egypt, Lydia and Phoenicia. The Milesian School which came from the region was the earliest school of ancient Greek philosophy. The Milesians were credited with bringing the first writing to Greece. Phoenicia was a name the Greeks gave to the Semitics that lived in the area of modern day Lebanon. The Semites were part of the older Canaanite culture. The Phoenicians were credited with bringing the first writing alphabet to the Greeks by Herodotus. However, Anaximander claimed that the Egyptians brought writing to Greece.12 It is now thought that writing arrived in Miletus around 750 BCE. In any case, writing began to take the place of hieroglyphics in many cultures long before the Greeks. The Phoenician alphabet was very similar to Hebrew at that time. The oral tradition went back well before writing arrived in Greece. The epic battles in Homer are thought to have occurred around the 13 century BC in the battle with Troy. Homer and Hesiod were recited verbally in hexameter by the rhapsodist.

[My comment: The transition from the oral tradition to writing has been the subject of much discussion even to the present time. Jacques Derrida in Of Grammatology argues that the transition from speech to writing displaced the speaker, the presence of the rhapsodist, of consciousness. This displacement was effectively a loss of an authorized origin, an arche. What replaced speech was a system of signs and differences, a yawning gap; perhaps in Hesiod’s cosmogony, chaos. The play of differences, of signs, in writing undoes the truth of presence and the signature of the speaker. It allows endless hermeneutics which disseminate truth, presence and origin. Could it be that what scholars refer to as the ‘anthropomorphic’ fixation of the gods in epic speech or rhapsody and the introduction of writing were not coincident in the transition to ‘logos’ but complicit? Could it be that pure consciousness as present in speech was displaced by writing so that the truth of the rhapsodist no longer sufficed as what ‘was’, the ‘real’ of ‘is-ness’, requiring a logos, a ‘logocentrism’ as Derrida suggests to become the thrust to re-authorize a canon based on phusis, the nature of being, the Idea (eidos) behind the shadow of consciousness? It is perhaps in this disruption we can catch a glimpse of the trace of “differance” (as Derrida writes) which plays as chaos, as an unthinkable gap which violently tears at the desire for origin, for arche.]

The primary philosophers in the Milesian School were: Thales (624 – 546 BCE), Anaximander (610 – c. 546 BCE) and Anaximenes of Miletus (585 – 528 BCE). These philosophers are typically thought as the first Greeks to start wondering what lies beneath appearance and change, phusis. The Milesian School did not want to understand what ‘is’ in terms of the gods. The Milesians were cynical about the ‘theologists’ of Homer and Hesiod’s time. However, it should be noted the chaos of Hesiod’s Theogony was not a God but more like a principle. The epic poets had more in common with the Milesians than some traditional scholars have acknowledged. The Milesians wanted to inquire into what could be seen, phusis, to understand what persists and what merely comes in and out accidentally of what ‘is’. The Milesians were early physicists.

These philosophers were looking for origins (arche). They suggested it was water, the infinite (apeiron) and air. They understood geometry and physical properties such as evaporation and condensation. They were looking for what remained the same in what appeared to change. They understood qualities could change like water could be solid as ice, misty as fog or liquid but all the qualities were still composed of water. Later, in Latin commentators, the ‘sameness’ was thought as ‘substance’. However, ‘substance’ has more modern connotations that did not necessarily apply to early Greek thinkers. The Milesian School is known as being hylozoistic. They thought of being, existence, and the universe as alive. Aristotle referring to Thales wrote, “Some say that soul is diffused throughout the whole universe; and it may have been this which led Thales to think that all things are full of gods.” (Arist., On the Soul or de Anima, i. 5 ; 411 a 7)13 They did not have the clear modern distinction of dead matter, of ‘it’ and some absolute neutrality we now easily think as ‘thing’. They were also called monists and animists as they were looking for universal principles and did not have a whole history that reduced and informed them that most of the universe was inanimate, lifeless and easily understood under the order of the ‘thing’. They still wondered at what we have already understood as ‘thing’ as having more, an excess, which could not be reduced to what we already know as a mere thing. While they may have disagreed about what that was, it is important to understand that it was not a settled matter but open and highly interesting. It is also interesting to note that even with the talk of modern physics telling us that they now understand very little of the universe in light of dark energy and dark matter, the underlying ontology, the unquestioned philosophy of being which already knows stuff as ‘thing’ and neutral, is still unsettled albeit, unquestioned by many. We would do well to incline our ears to a beginning in which these notions were still unsettled and open.

The Milesians marked the beginning of the transition from mythos to logos according to classic scholarship. Logos is our modern word for logic but our modern notion of logic is very different from what the ancient Greeks thought as logos. In the later Greek thinking of Aristotle, logos is what allows phusis (what lies forth14) to be gathered into itself as what appears and what does not appear in the phenomenon (phainomenon; what shows itself or comes to light). However, at the time of Thales logos was a verbal account or reckoning. Speech was common to humans. We talk to one another and do not solely create private languages that no else can comprehend. This made the logos appear to have a ‘sameness’ that made it understandable to others. Because of this, the logos would become increasingly more interesting for Greek philosophers and the questioning of phusis. Heraclitus, a student of Anaximander, was thought to have stated, “For this reason it is necessary to follow what is common. But although the LOGOS is common, most people live as if they had their own private understanding.”(Diels-Kranz, 22B2) Already, early on, Greek philosophers realized that logos exhibited an interesting tension between commonality and individuality, the many and the one.

Philosophy Series 4 – The Pre-Socratics – Hesiod

_________________

1 See Link

2 See Link

3 See Link

4 See Link

5 See Link (pdf)

6 See Link (pdf)

7 Roger D. Woodard (2008), “Greek dialects”, in: The Ancient Languages of Europe, ed. R. D. Woodard, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 51.

8 See Link

9 See Link

10 One can even set up quite ridiculous cases. A cat is penned up in a steel chamber, along with the following device (which must be secured against direct interference by the cat): in a Geiger counter, there is a tiny bit of radioactive substance, so small that perhaps in the course of the hour, one of the atoms decays, but also, with equal probability, perhaps none; if it happens, the counter tube discharges, and through a relay releases a hammer that shatters a small flask of hydrocyanic acid. If one has left this entire system to itself for an hour, one would say that the cat still lives if meanwhile no atom has decayed. The psi-function of the entire system would express this by having in it the living and dead cat mixed or smeared out in equal parts. It is typical of these cases that an indeterminacy originally restricted to the atomic domain becomes transformed into macroscopic indeterminacy, which can then be resolved by direct observation. That prevents us from so naively accepting as valid a “blurred model” for representing reality. In itself, it would not embody anything unclear or contradictory. There is a difference between a shaky or out-of-focus photograph and a snapshot of clouds and fog banks.

—Erwin Schrödinger, Die gegenwärtige Situation in der Quantenmechanik (The present situation in quantum mechanics), Naturwissenschaften

(translated by John D. Trimmer in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society) See Link

12 See The Greek Concept Of Nature By Gérard Naddaf here, page 103

13 See this

14 Phusis, therefore, is what has been said. And everything that contains within itself an emerging and governing (arche) which is constituted in this way `has’ phusis. And each of these beings is (has being) in the manner of beingness (ousia). That is to say, phusis is a lying-forth from out of itself (hupokeimenon) of this sort and is in each being which is lying-forth. However, each of these beings, as well as everything which belongs to it in and of itself is in accordance with phusis. For example, it belongs to fire to be borne upward. That is to say, this (being borne upward) is certainly not phusis, nor does it contain phusis, but rather it is from out of phusis and in accordance with phusis. Thus what phusis is is now determined as well as what is meant by `from out of phusis’ and in accordance with phusis. (Physics 192 b3z-i93 az; WBP 329)

Walter A. Brogan. Heidegger And Aristotle: The Twofoldness Of Being (Kindle Locations 774-779). Kindle Edition.