With regard to the paper, “the Microeconomic Foundations of Macroeconomic Disorder: An Austrian Perspective on the Great Recession of 2008” by Steven Horwitz at this link he states:

It is true that the problematic loans that were at the bottom of all the current recession were generated by banks and mortgage companies and not Fannie and Freddie. However, their presence as “Big Players” in the mortgage market dramatically distorted the incentives facing those truly private actors. Their willingness and ability to buy up mortgages originated by others made private actors far more willing to make risky loans, knowing they could quickly package them up and sell them off to Fannie, Freddie, and others. Fannie and Freddie had both various Government privileges and the implicit promise of tax dollars if need be. This combination enabled them to act without the normal private sector concerns about risk and reward, and profit and loss. Their relative immunity from genuine market profit and loss sent distorting ripple effects through the rest of the mortgage industry, allowing the excess loanable funds coming from the Fed to be turned into a large number of mortgages that probably never should have been written.

Other regulatory elements played into this story. Fannie and Freddie were under significant political pressure to keep housing increasingly affordable (while at the same time promoting instruments that depended on the constantly rising price of housing) and extending opportunities to historically “under-served” minority groups. Many of the new no/low downpayment mortgages (especially those associated with Countrywide Mortgage) were designed as responses to this pressure. Throw in the marginal effects of the Community Investment Act, which required lenders to serve those under-served groups, and zoning and land-use laws that pushed housing into limited space in the suburbs and exurbs and driving up prices in the process, and you have the ingredients of a credit-fueled and regulatory-directed housing boom and bust. This variety of government policies and regulations was responsible for steering this particular boom in the direction of the housing market. Unlike past booms where the excess of loanable funds ended up as credit to producers, this set of unique events that accompanied this boom was responsible for channeling those funds into housing.

I think it is important to quantify or at least draw perspective from some statistical data how much the “Big Players” contributed to the recession of 2008.

From my own research, previously I this material from the Center for American Progress and the Atlantic which sided with the Federal Government’s commission findings that multiple issues contributed to the outset of the recession. These groups cast significant doubts on some of the early data propagated by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a conservative think tank, specifically in papers written by Peter Wallison and Edward Pinto. The Federal Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC), a equally partisan commission set up by the U.S. Government, cited many different conditions for the crisis. AEI started down a path long before the report came out that tried to substantiate claims that the Federal Government was the primary cause of the recession not the private market or international markets. Wallison was one of the dissenters on the commission’s final report. Here are some statistical anomalies the Center for American Progress pointed out:

Pinto’s controversial conclusion that federal housing policies were responsible for 19 million high-risk mortgages is based on radically revised definitions for the two main categories of high-risk mortgages, subprime loans and so-called Alt-A mortgages, which refer to loans with low documentation of income and wealth. Importantly, these revised definitions are not consistent with how the terms subprime and Alt-A are used for data collection.

As a result of his dramatically expanded new definitions that are not used by other leading scholars, Pinto’s findings on the extent of subprime and Alt-A exposure are extreme outliers among mortgage market analysts. Pinto’s claim that there were 26.7 million subprime and Alt-A loans outstanding (out of roughly 55 million total) as of June 30, 2008, is exponentially higher than other estimates. In a 2010 report, the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office, the research arm of Congress, found there were only 4.58 million subprime and Alt-A mortgages outstanding at the end of 2009, less than one-fifth of Pinto’s estimate.

Similarly, Pinto’s claim that 19 million, or 72 percent of all “subprime” and “Alt-A” mortgages were attributable to federal affordable housing policies is far afield of the conclusions of other analysts. The claim is also difficult to reconcile with the actual data, which indicate the entire federal government (including Fannie and Freddie) owned or guaranteed only 32 percent of seriously delinquent loans despite holding 67 percent of all mortgages. Pinto’s claim that Fannie and Freddie were the primary driver of high-risk mortgages does not stand when the evidence is weighed accurately.

Because of Pinto’s anomalous findings, Wallison largely elides over the role of so-called “private-label” mortgage-backed securities in causing the crisis despite the large amount of attention these financial instruments received elsewhere, including in the FCIC majority’s report. This private mortgage financing channel, which does not involve the federal government at all and was policed only minimally, generated only 13 percent of outstanding loans but was responsible for 42 percent of serious delinquencies.

Pinto makes numerous other serious errors in his analysis. Case in point: In analyzing the influence of the Community Reinvestment Act, a 1977 antidiscrimination law that simply requires regulated banks and thrifts to lend nondiscriminatorily to low- and moderate-income borrowers and communities within the immediate geographic areas surrounding branch offices of a deposit-taking institution, Pinto includes a large quantity of loans that were not required by CRA or any other equivalent law or regulation. This mistake, coupled with some unsupported assumptions about the riskiness of CRA loans, produces a shockingly high estimate of 2.24 million “subprime” and “high-risk” loans attributable to CRA. This compares to a finding of 378,000 CRA-eligible loans originated during the housing bubble by other leading researchers.

Pinto also wrongly blames the affordable housing goals of Fannie and Freddie for the origination of Alt-A loans, which under his analysis account for 65% of the “high risk” mortgages attributable to Fannie and Freddie. In fact, these Alt-A loans (either according to the normal usage of “Alt-A” or Pinto’s newly invented definition of “Alt-A”) would not have qualified for the affordable housing goals.

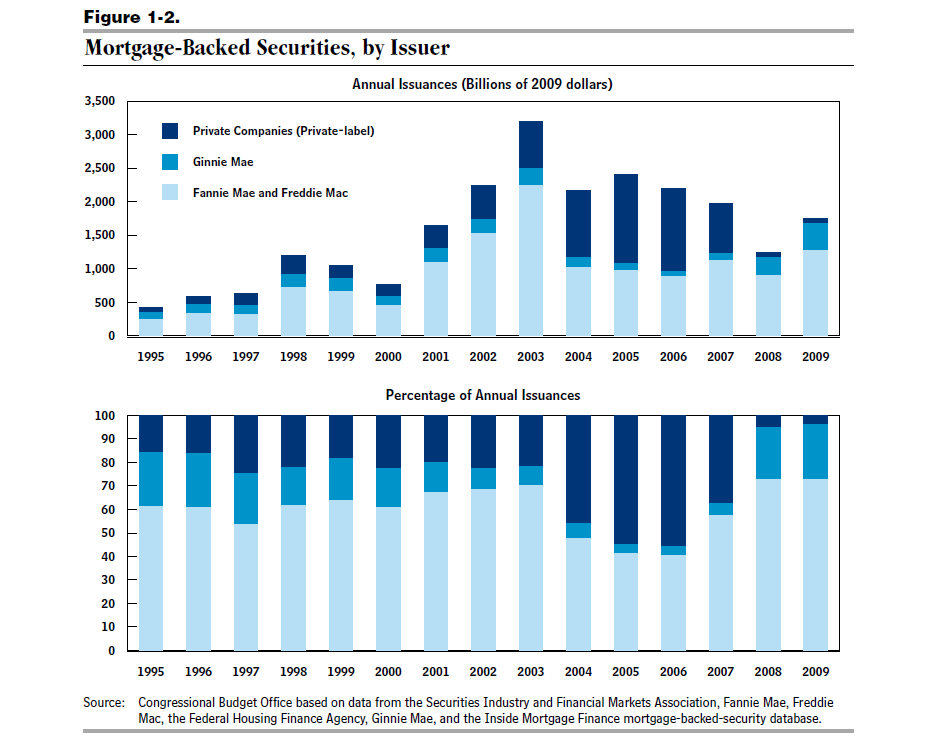

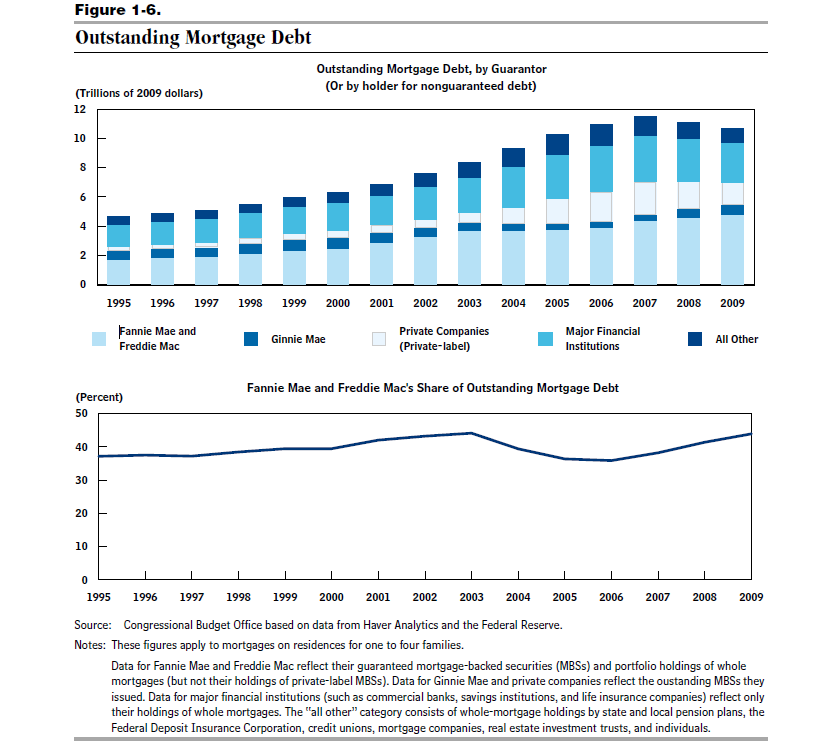

In my research data, there are many more charts and reports from conservative, moderate and non-partisan groups such as the GAO. There is also data on the later SEC lawsuit. In any case, the data below illustrates Congressional Budget Office (CBO) data for mortgage backed securities (MBS) before and during the crisis years.

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Role in the Secondary Mortgage Market, December 2010, Link Chapter 1, page 7, page 27 in pdf

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Role in the Secondary Mortgage Market, December 2010, Link Chapter 1, page 11, page 31 in pdf

This data clearly shows that the private market issued a substantially higher percentage of MBS from previous years from 2004 to 2007.

Additionally, the FCIC final report stated:

“The number of suspicious activity reports—reports of possible financial crimes filed by depository banks and their affiliates—related to mortgage fraud grew 20-fold between 1996 and 2005 and then more than doubled again between 2005 and 2009. One study places the losses resulting from fraud on mortgage loans made between 2005 and 2007 at 112 billion.” (report, page xxii)

The argument Steven Horwitz makes is that this amount of holdings by the GSEs distorted the normal checks and balances of the market to the point where, in addition to Greenspan’s driving up the money supply and driving down the interest rates, resulted in his conclusion:

From an Austrian perspective, the eventual collapse of this house of cards built on inflation represents not a failure of capitalism, but a largely predictable failure of central banking and other forms of government intervention.

The conclusion of the FCIC report states that, “Nearly 11 trillion in household wealth has vanished, with retirement accounts and life savings swept away.” Worldwide the bubble resulted in investor loses conservatively from 30 trillion dollars to estimates over 100 trillion dollars all from an annual several trillion dollar U.S. housing market during the crisis years (see this data for more details-please note that my positions have changed over the years I have been researching this). One of the dissenters to the final report stated that,

Starting in the late 1990s, China, other large developing countries, and the big oil-producing nations built up large capital surpluses. They loaned these savings to the United States and Europe, causing interest rates to fall. Credit spreads narrowed, meaning that the cost of borrowing to finance risky investments declined. A credit bubble formed in the United States and Europe, the most notable manifestation of which was increased investment in high-risk mortgages. U.S. monetary policy may have contributed to the credit bubble but did not cause it.

From all these various data sources it is hard to see how U.S. Government intervention in the U.S. market could lead to all the international consequences without postulating some sort of massive amplification mechanism. The proportions from the documented GSE’s market share to the private U.S. mortgage market share totals to the financial crisis investor loss totals worldwide seem to make it an uphill climb to pin it all or primarily on the U.S. Government. Additionally, the cause and effect appears hard to establish with the worldwide timing of the recession. This makes me inclined to believe the FCIC’s conclusion more which listed multiple causes for the recession including the private market’s proportionally, vastly larger financial products contribution to the recession over the smaller mortgage backed securities created by the GSE’s.(1.) In order to believe Steven Horwitz we would have to buy a couple premises:

- The bust of a recession can be much larger than the boom and even uncorrelated as a one on one relationship (although it seems to have higher correlation when the government is involved).

- The effects of the recession can primarily start in one place (i.e., the U.S. Federal Government) and simultaneously bust out in countries all over the world (especially when the U.S. Government is involved).

- A priming effect (i.e., the distortion of market risk by government intervention) can spill over into many different private market segments such as private market, financial products and reap havoc on investors (again, the U.S. Government seems to do this particularly well compared to private industry).

- The effect can lead the cause as “the housing bubble occurred during a period when Fannie and Freddie’s market share dropped precipitously” (see note (1.) below)

On one hand, the free market advocates want to make the claim that the market is robust and self-correcting. However, a certain kind of ‘over sensitivity’ seems to apply when the government has anything to do with the market. I assume some further distinctions need to be made with different types of government interventions such as government bonds, monetary interventions, private company bail outs, regulations (including anti-piracy, monopolies, environmental,…), market subsidies, etc. Internationally, we know that large countries recently (and historically) have regularly propped up their economies by devaluing their currencies or subsidizing industries and whole market segments that would never make it in a real free market but the U.S. Government seems to be really good at mucking the rest of the world up relative to its interventions according to Steven Horwitz. There is also the issue of large, private U.S. companies that effectively operate with the same vices as the U.S. Government such as de facto private market regulation that prohibit competition, buying and destroying companies for market share, monopolizing resources that prevented competition, etc. (see this). The companies can be multinational corporations and yet still seemingly have relatively normative free market consequences that poses no threat or much less of a threat than the U.S. Government.

Actually, I am in sympathy with much of the microeconomic direction of the Austrian school of economics that he advocates. I also really like the idea he states that,

Austrians have been very critical of the equilibrium orientation of modern economics and have, instead, tried to understand markets as open-ended evolutionary systems. There’s no objectively correct pattern of resource allocation out there. Rather, as James Buchanan put it, “order is defined in the process of its emergence.” Just as biological evolution doesn’t produce the “perfect squirrel” but one well-adapted to its environment, the same is true of markets.

This fits very nicely into post modernism I think. I have always liked the small scale, community based systems of organization such as idealized in Marx, distributivism and agrarian economics, etc. but I find one troubling dilemma in thinking of these in macroeconomic terms, -they seem to be utopist and not reflective of reality.

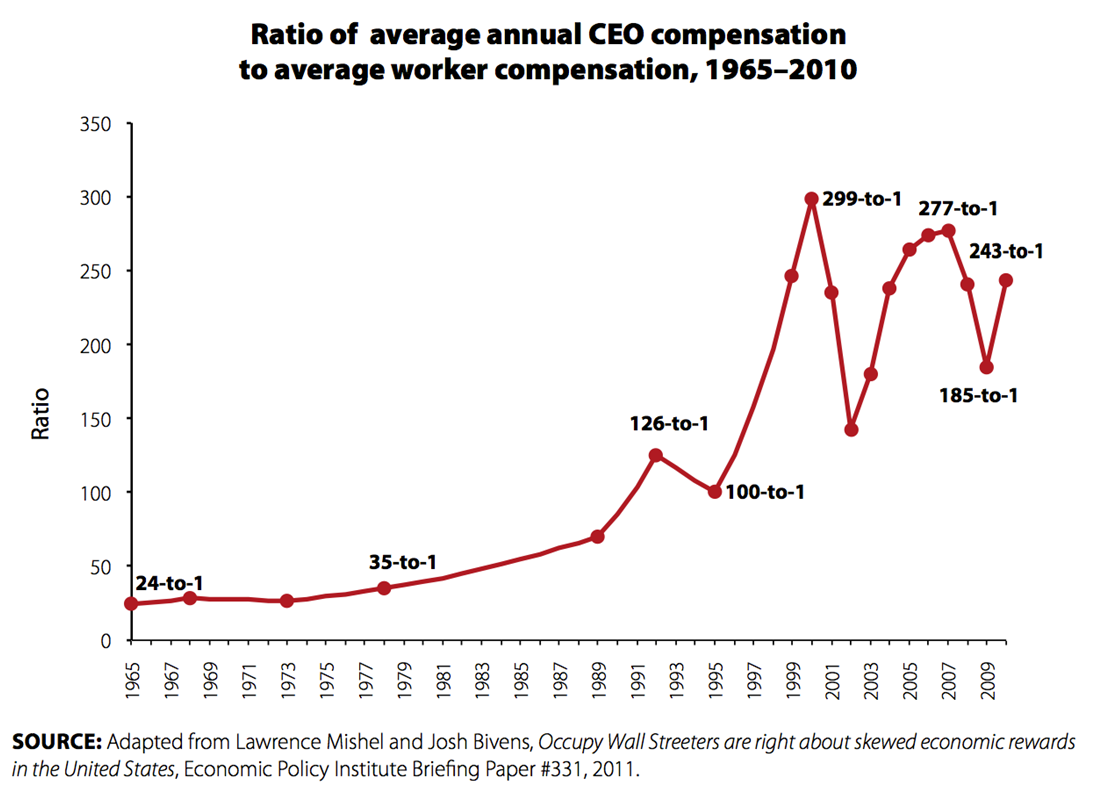

One example is the way in which capital in the form of wages and salaries is so out of proportion from laborers to CEOs, hedge fund managers, financial industry managers, etc.

See this link

Steven Horwitz describes his view of wages from a couple economists, Hutt and Say. In this quote he illustrates how idleness (i.e., unions) could artificially intervene in the normative market process using coercive means to artificially inflate wages against normative market price support.

Although Hutt (1977 [1939]) distinguishes among a number of different forms of idleness, in general they break down into three categories: (1) preferred idleness, (2) pseudo-idleness, and (3) price-driven idleness. The first category is straightforward: Some people simply have a strong preference for leisure and are willing to exercise it. The second category refers to workers or assets which appear to be idle but are actually producing something. One example is an “unemployed” worker who is actively engaged in a job search. Such searches are productive activity, “prospecting” as Hutt calls it, and the worker is therefore not truly idle. Other examples are balances of money or stocks of inventory. Both are “idle” in some physical sense, yet both produce the service of “availability.” That is, both are there waiting to be used when needed. We would not, analogously, wish to call a fire truck waiting in a fire station “idle.” Rather it is doing its job – being available when needed. The third category is the one of great theoretical and policy concern. This category lumps together a number of Hutt’s own categories, but what it generally is referring to is the idleness created when some or all of the factors of production are able to coercively maintain wages or prices above market-clearing levels. By forcing producers to pay all workers hired a wage greater than what would obtain in a competitive market, labor creates idleness both in those workers in the given industry who are not hired at the higher wage and in those workers in other industries who are let go because of the contraction of the wages and income flows which result. It is this last form of idleness which concerns Hutt the most.

Labor Market Coordination and Monetary, Equilibrium: W H. Hutt’s Place in “Pre-Keynesian” Macro, STEVEN HORWITZ, St. Lawrence University, Canton, NY 13617, Page 211

Here he describes Say’s fundamental ‘Law of Markets’ as concisely stated, “Production is the source of demand.”

“My ability to demand food, clothing, and shelter derives from the productivity of my labor or my non-labor assets. The lower (higher) that productivity, the lower (higher) is my power to demand. Hutt (1975, p. 27) states this as” “All power to demand is derived from production and supply” (IBID, page 213)

Here is Hutt’s explanation for how entrepreneurs determine workers wages:

If the entrepreneurial pessimism is justified, then the proper result is a decline in wages. Resisting those wage reductions is ultimately a mistake for workers since idleness will result and the total wages flow will fall, reducing demand and wages and/or employment in noncompeting markets. If the pessimism was mistaken, markets contain a built-in correction mechanism which will kick in if workers accept the wage cuts. As entrepreneurs discover that their pessimism was unwarranted, the larger than expected demand for their product will put upward pressure on prices and The entrepreneur pays wages based on market expectations and his calculation wages, driving wage rates back to the appropriate level. Once again, resisting the original wage cuts, even if entrepreneurs are mistaken, only creates more problems than accepting them. Although entrepreneurs may be in error, there is likely no one else in a better position to form accurate expectations of the future? The ultimate source of idleness is not deficient aggregate demand, but barriers to coordination through market pricing. (IBID, page 215 – 216)

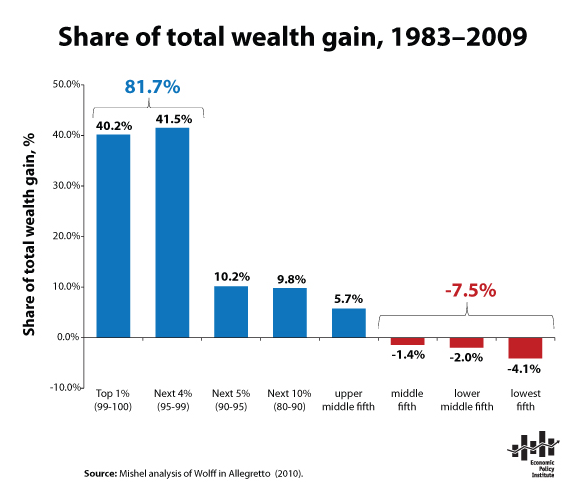

From this we can see that workers wages are, in a pure free market, determined solely by their ‘production’ or their “non-labor assets”. Since “non-labor assets” are typically not very high for the average worker, their ability to demand is mostly a function of their ability to produce. However, when we think about recent examples of highly paid executives that can not only not produce but lose billions and still get huge bonuses and salaries for the ‘production’, it appears that there is a different mechanism at work. I have not found Steven Horwitz explanation of this mechanism yet but I assume it would go something like this…the market is imperfect and messy and over time will correct these ‘anomalies’. However, it does seem that these ‘anomalies’ happen more often for those with the highest wealth than those with the lowest wealth.

Additionally, I wonder if he would suggest that the wealthy have huge “non-labor assets” that is not idle, abstract capital but heterogeneously committed capital. I wonder if he would suggest that this wealth is not sitting idly in passbook savings accounts or overseas accounts but invested in job creation. Therefore, since they produce more they can demand more. This all seems logical but inconsistent in view of how when they win, they win and when they lose, they also win at least in some well publicized cases and recent decades of historical data on the how the wealthy have increased their wealth dramatically in spite of the recession.

See this link

Apparently, the mechanism that explains the demand and production for the wealthy needs some further work or explanation.

In any case, I do not see how the free market, self correcting and regulating mechanisms, work to provide some modicum of equality over the range from the bottom to the top. At some point it seems that wealth tends to get distributed upward in capitalism without any real restraint that the hyperbole of capitalism’s proponents would like to bring to the fore. Where are the checks and balances here or is this yet another case of government intervention mucking up things? Why isn’t the malformation of reward in the free market considered a ‘bubble’ of sorts…because it is permanent perhaps? It appears that many economists barely mention this phenomenon or just excuse it as a kind of unlimited upside of free market, entrepreneurial success. If capitalism is evolution then we should see the laborer ‘species’ die off and the manager species take off genetically. However, the manger species seems to need the laborer species to hang around…perhaps as moss needs a tree. In any case, at some point this symbiotic condition appears more like slavery than evolution. Some economists even seem to go so far as to suggest that the laborer creates real value in capitalism but they always stop short in explaining why the systems cannot or will not reward real value. Why are athletes rewarded more than teachers? Is the teacher species going away and we can watch football in its place? This direction of questions is aimed at understanding how capitalism correctly (in the long run) dispenses value (or the Austrian school’s notion of heterogeneous capital). If capital is not abstract but real, tied to specific investments and labor, how is it that astronomical numbers for one person’s salary are much more than most people can ever comprehend?

I understand that they willingly admit that the system is imperfect, sluggish, wrong at times, etc. but somehow they come up with an overall justification for its continued existence and merit. In the long run they seem to have faith that inequities will get straightened out without any extra-market intervention so I suppose in the long run teachers will get more than athletes or CEOs but it is hard to see a scenario in which that could happen. I suppose I would wonder what does ‘straighten out’ mean? Does this mean that unbelievably high salaries will continue to go exponentially out of the stratosphere as it has for some time now? Does it mean that the plumber will be the highest paid worker in the U.S. in a few hundred years? I suppose in evolution there are times in a species evolution where they disappear, is this how it will get straightened out? Or perhaps, the same old way it has always gotten straightened out, a revolution? In Austrian economics it seems we can avoid boom and bust cycles to a large degree by getting rid of government interventions (of all types…government bonds, monetary interventions, private company bail outs, regulations (including anti-piracy, monopolies, environmental,…), market subsidies, etc…or of some types?). However, it appears that equity gets redefined as what simple happens that gets deemed and endued as the right outcome or simply a line in a CEO’s profit and loss statement. Who are we to question or muck with evolution? The prescription is the description but really it cannot be prescriptive at all as the ‘process of emergence produces the order’ and who are we to want to change it with an alien influence like government? Have you ever seen a tree wind and accommodate its rhizome around a chain fence? In evolution it seems that adaptation to alien influences does not hinder survival but actually can enhance it and make it stronger. However, when it comes to the free market and government intervention, evolution has met its match and can find no way to adapt or incorporate its environment…or could it be that in Austrian economics a meta-language that pre-ordains and determines inevitable outcomes has found a convenient (for some) and privileged rank? It would seem that the “order [that] is defined in the process of its emergence” has some ancillary determinations as well.

************************

-

This point has been dealt with in more detail in links cited but here is some additional information:

“The GSEs participated in the expansion of subprime and other risky mortgages, but they followed rather than led Wall Street and other lenders in the rush for fool’s gold. They purchased the highest rated non-GSE mortgage-backed securities and their participation in this market added helium to the housing balloon, but their purchases never represented a majority of the market. Those purchases represented 10.5% of non-GSE subprime mortgage-backed securities in 2001, with the share rising to 40% in 2004, and falling back to 28% by 2008.” (FCIC Conclusion, page xxvi)

“The Commission concludes the CRA was not a significant factor in subprime lending or the crisis. Many subprime lenders were not subject to the CRA. Research indicates only 6% of high-cost loans—a proxy for subprime loans—had any connection to the law. Loans made by CRA-regulated lenders in the neighborhoods in which they were required to lend were half as likely to default as similar loans made in the same neighborhoods by independent mortgage originators not subject to the law.” (FCIC Conclusion, page xxvii; see also this and this)

“2. TIMING IS EVERYTHING

Second, Wallison fails to inform his readers that Wall Street’s “private-label securitization” of mortgages, which objective analysts identify as the primary source of most subprime and other high-risk loans, experienced a dramatic increase in market share that was exactly contemporaneous with the housing bubble, rising from about 10 percent market share in 2003 to nearly 40 percent by 2006. Overall, loans originated for private-label securitization have defaulted at about six times the rate of Fannie and Freddie loans. Indeed, Wallison does not explain–cannot convincingly explain–why the housing bubble occurred during a period when Fannie and Freddie’s market share dropped precipitously. Wallison’s answer to this central problem with his thesis is simply to claim that the housing bubble began in the early 1990s (Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner, who advance a similar argument about the central role of Fannie and Freddie’s affordable housing goals in the housing bubble in their book Reckless Endangerment, deal with this problem in a different, but equally anemic way–claiming that Fannie and Freddie created a “cultural” shift in mortgage banking, teaching Wall Street that lobbying and increased risk-taking could lead to greater profits).” (The Atlantic)