In my continuing investigation on the economic crisis that started during the last decade I have more results and links to report. This data is fairly raw and is meant to be more of a resource for others. I am trying to include information in this that gives all sides of the issue. It represents a fairly large time investment to go through this but I do think, in this case, learning from the past is absolutely necessary.

First, let’s back up.

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) is a ten-member commission appointed by the United States government with the goal of investigating the causes of the financial crisis of 2007–2010.

Here is how it was composed:

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi of California and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada each made three appointments, while House Minority Leader John Boehner of Ohio and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky each made two appointments:

Phil Angelides (chairman) – Pelosi (jointly chosen as chair by Pelosi and Reid)

Bill Thomas (vice chairman) – Boehner (jointly chosen as vice chair by Boehner and McConnell)

Brooksley Born (Pelosi)

Byron Georgiou (Reid)

Bob Graham (Reid)

Keith Hennessey (McConnell)

Douglas Holtz-Eakin (McConnell)

Heather Murren (Reid)

John W. Thompson (Pelosi)

Peter J. Wallison (Boehner)

As you can see the committee was bipartisan in composition.

The Commission reported its findings in January 2011.

The commission found a wide range of breakdowns that resulted in the crisis.

The conclusion is well worth the read but here is a synopsis from the Wiki link above:

The Commission concluded that “the crisis was avoidable and was caused by: Widespread failures in financial regulation, including the Federal Reserve’s failure to stem the tide of toxic mortgages; Dramatic breakdowns in corporate governance including too many financial firms acting recklessly and taking on too much risk; An explosive mix of excessive borrowing and risk by households and Wall Street that put the financial system on a collision course with crisis; Key policy makers ill prepared for the crisis, lacking a full understanding of the financial system they oversaw; and systemic breaches in accountability and ethics at all levels.” There were two dissents. One is here. Another dissent by Peter Wallison, on the commission, claimed that the crisis was caused by government affordable housing policies rather than market forces. Wallison was also with the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a very conservative think tank.

Edward Pinto, a former Fannie May credit officer, also worked with Wallison. He also worked at AEI. Here is his report on the crisis.

Wallison’s views have been seriously challenged by subsequent detailed analyses of mortgage market data (and Center for American Progress).

Here are some excerpts from the Center for American Progress paper.

“Unfortunately, Pinto’s research findings relied upon so heavily by Wallison and others are false. Pinto’s work is based on a series of faulty assumptions and serious methodological flaws. Pinto’s controversial conclusion that federal housing policies were responsible for 19 million high-risk mortgages is based on radically revised definitions for the two main categories of high-risk mortgages, subprime loans and so-called Alt-A mortgages, which refer to loans with low documentation of income and wealth. Importantly, these revised definitions are not consistent with how the terms subprime and Alt-A are used for data collection, as this paper will demonstrate.

As a result of his dramatically expanded new definitions that are not used by other leading scholars, Pinto’s findings on the extent of subprime and Alt-A exposure are extreme outliers among mortgage market analysts. Pinto’s claim that there were 26.7 million subprime and Alt-A loans outstanding (out of roughly 55 million total) as of June 30, 2008, is exponentially higher than other estimates. In a 2010 report, the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office, the research arm of Congress, found there were only 4.58 million subprime and Alt-A mortgages outstanding at the end of 2009, less than one-fifth of Pinto’s estimate.

Similarly, Pinto’s claim that 19 million, or 72 percent of all “subprime” and “Alt-A” mortgages were attributable to federal affordable housing policies is far afield of the conclusions of other analysts. The claim is also difficult to reconcile with the actual data, which indicate the entire federal government (including Fannie and Freddie) owned or guaranteed only 32 percent of seriously delinquent loans despite holding 67 percent of all mortgages. Pinto’s claim that Fannie and Freddie were the primary driver of high-risk mortgages does not stand when the evidence is weighed accurately.

Because of Pinto’s anomalous findings, Wallison largely elides over the role of so-called “private-label” mortgage-backed securities in causing the crisis despite the large amount of attention these financial instruments received elsewhere, including in the FCIC majority’s report. This private mortgage financing channel, which does not involve the federal government at all and was policed only minimally, generated only 13 percent of outstanding loans but was responsible for 42 percent of serious delinquencies.

Pinto makes numerous other serious errors in his analysis. Case in point: In analyzing the influence of the Community Reinvestment Act, a 1977 antidiscrimination law that simply requires regulated banks and thrifts to lend nondiscriminatorily to low- and moderate-income borrowers and communities within the immediate geographic areas surrounding branch offices of a deposit-taking institution, Pinto includes a large quantity of loans that were not required by CRA or any other equivalent law or regulation. This mistake, coupled with some unsupported assumptions about the riskiness of CRA loans, produces a shockingly high estimate of 2.24 million “subprime” and “high-risk” loans attributable to CRA. This compares to a finding of 378,000 CRA-eligible loans originated during the housing bubble by other leading researchers.

Pinto also wrongly blames the affordable housing goals of Fannie and Freddie for the origination of Alt-A loans, which under his analysis account for 65% of the “high risk” mortgages attributable to Fannie and Freddie. In fact, these Alt-A loans (either according to the normal usage of “Alt-A” or Pinto’s newly invented definition of “Alt-A”) would not have qualified for the affordable housing goals.

As this paper will demonstrate, these and many other similar methodological flaws are fundamentally embedded in Pinto’s research, making his conclusions fundamentally unreliable and essentially useless for the purpose of understanding either the causes of the housing bubble or the high rates of delinquencies that have occurred during the housing downturn. Yet based in large part on the inaccurate and misleading data peddled by Pinto, many policymakers are advocating inapt and often counterproductive solutions to the financial crisis.

This paper is designed to set the record straight on the following specific claims by Pinto that are either wrong or grossly distorted, and to highlight the extremely shaky foundation for the argument found in Wallison’s FCIC dissent that federal affordable housing policies caused the financial crisis.”

Here is another refutation from The Atlantic

“To understand why Wallison’s argument has been rejected by many analysts, including by all nine of his fellow commissioners on the FCIC, it is helpful to recall a few facts that he conspicuously omits from his interview with the Atlantic.

1. A SUBPRIME DEFINITION OF ‘SUBPRIME’

First, central to Wallison’s argument that affordable housing policies (including those advocated by Rep. Frank in 1992) caused the mortgage crisis is his claim that the federal government is responsible for 19.2 million “subprime” mortgages (with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac being responsible for 12 million of those). But what Wallison fails to tell the Atlantic’s readers is that he is using his own made-up definition of “subprime,” a definition that no one outside of his think tank, the American Enterprise Institute, uses. By way of comparison, the non-partisan Government Accountability Office has estimated that there were only 4.58 million subprime and other high risk loans outstanding, with very few of these attributable to the federal government.

Importantly, as I’ve argued elsewhere, Wallison’s vastly expanded definition of “subprime” does not stand up to serious scrutiny. In fact, the overwhelming majority of the “subprime” loans Wallison attributes to the federal government have defaulted at about the same rate as the national average. This delinquency rate is about one-third the rate of actual subprime mortgages.

Wallison also omits the fact that most of the “subprime” mortgages he attributes to federal affordable housing policies could not have been motivated by these policies, either because the loans were ineligible (typically because they were made to higher-income borrowers) or because the lenders were not subject to these policies (such as in the case of the non-bank lenders, which did not have any applicable federal affordable housing requirements; non-bank lenders made up 24 of the top 25 subprime lenders in 2006).

2. TIMING IS EVERYTHING

Second, Wallison fails to inform his readers that Wall Street’s “private-label securitization” of mortgages, which objective analysts identify as the primary source of most subprime and other high-risk loans, experienced a dramatic increase in market share that was exactly contemporaneous with the housing bubble, rising from about 10 percent market share in 2003 to nearly 40 percent by 2006. Overall, loans originated for private-label securitization have defaulted at about six times the rate of Fannie and Freddie loans. Indeed, Wallison does not explain–cannot convincingly explain–why the housing bubble occurred during a period when Fannie and Freddie’s market share dropped precipitously. Wallison’s answer to this central problem with his thesis is simply to claim that the housing bubble began in the early 1990s (Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner, who advance a similar argument about the central role of Fannie and Freddie’s affordable housing goals in the housing bubble in their book Reckless Endangerment, deal with this problem in a different, but equally anemic way–claiming that Fannie and Freddie created a “cultural” shift in mortgage banking, teaching Wall Street that lobbying and increased risk-taking could lead to greater profits).

3. WHAT CAUSED THE COMMERCIAL BUBBLE?

Third, Wallison ignores the parallel bubble-bust cycle we experienced in commercial real estate, which does not have affordable housing policies of the sort he criticizes for Fannie and Freddie. Commercial real estate values experienced a peak-to-trough price decline of 45 percent, which was considerably worse than the 33 percent peak-to-trough price decline we saw in residential real estate. If, as Wallison contends, it was affordable housing policies that caused the residential real estate bubble, then what caused the bubbles in commercial real estate? Moreover, why did we have similar surges in credit liquidity in student loans, auto loans, and credit cards? The mainstream narrative advanced by Rep. Frank and most others–that it was unregulated securitization on Wall Street that drove the financial crisis–explains these parallel bubbles fairly well; the argument advanced by Wallison does not.

Moreover, as Wallison’s fellow Republican-appointed commissioners on the FCIC noted, many other countries, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Ireland, and the United Kingdom, all had contemporaneous housing bubbles. Again, the mainstream narrative–that poorly regulated new forms of financing drove asset bubbles–explains this fact rather well; Wallison’s argument does not.

In short, there are many reasons, of which I’ve provided just a few, why Peter Wallison’s argument has been rejected by his fellow Republican-appointed FCIC commissioners.

Unfortunately, some people will, for ideological and other reasons, always believe that any market failures must necessarily be the fault of government intervention, no matter how convincing and overwhelming the evidence is against this proposition. I believe we should join with the more nuanced view taken by Rep. Frank, who has rejected the proposition that U.S. housing policies caused the financial crisis, while at the same time acknowledging that these policies were flawed and need major revisions.

_________________________________________

Editor’s Update: Peter Wallison responds via email.

“Now that the SEC has sued Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for failure to disclose the subprime and other low quality loans they held and securitized, this really is the last time we’ll hear from David Min and others who have been trying to protect the government from blame for the financial crisis.

“The SEC’s suit is based on the failure of Fannie and Freddie to disclose the poor quality of the mortgages that they were buying, holding and securitizing. As the SEC said in its press release on the suit: “Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac executives told the world that their subprime exposure was substantially smaller than it really was.” This explains why Min and others–despite the insolvency of Fannie and Freddie– have continue to argue that the two companies did not hold substantial amounts of subprime and other low quality loans. Fannie and Freddie simply failed to disclose this information.

“The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission failed completely in its mission because it refused to inquire seriously into what Fannie and Freddie had done. My dissent however, based on the research of my AEI colleague Edward Pinto, contains all this data, and even points out that Fannie and Freddie had failed to disclose it to the market. Although the FCIC had subpoena power and could have put Fannie and Freddie executives under oath, the FCIC did not want to know the facts that the SEC has now discovered. It was a travesty and a whitewash, and a waste of taxpayer funds. It has also misled people like David Min and others into believing that Fannie and Freddie were–as the FCIC said in its majority report–only “marginal” players in the financial crisis. It’s lucky for the FCIC that the SEC doesn’t have jurisdiction over false government reports.

“When all the facts come out at trial, the roles of Fannie and Freddie, and the government housing policies they were implementing, will become painfully clear.””

The note at the end of this brings up the issue of 6 former GSE executives charged by the SEC with understating the sub-prime exposure of the GSEs.

Here are some articles of this topic:

http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2011/2011-267.htm

http://www.fedfin.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=797&Itemid=30

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/24/opinion/nocera-the-big-lie.html

http://blogs.reuters.com/bethany-mclean/2012/01/17/a-tale-of-two-sec-cases/

“But Pinto’s numbers don’t hold up. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission(FCIC) – Wallison was one of its 10 commissioners – met with Pinto and analyzed his numbers, and concluded that while Fannie and Freddie played a role in the crisis and were deeply problematic institutions, they “were not a primary cause.” (Wallison issued a dissent.) The FCIC argued that Pinto overstated the number of risky loans, and as David Min, the associate director for financial markets policy at the Center for American Progress, has noted, Pinto’s number is far bigger than that of others – the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office estimated that from 2000 to 2007, there were only 14.5 million total nonprime loans originated; by the end of 2009, there were just 4.59 million such loans outstanding.

The disparity stems from the fact that Pinto defines risky loans far more broadly than most experts do. Min points out that the delinquency rates on what Pinto calls subprime are actually closer to prime loans than to real subprime loans. For instance, Pinto assumes that all loans made to people with credit scores below 660 were risky. But Fannie- and Freddie-backed loans in this category performed far better than the loans securitized by Wall Street. Data compiled by the FCIC for a subset of borrowers with scores below 660 shows that by the end of 2008, 6.2 percent of those GSE mortgages were seriously delinquent, versus 28.3 percent of non-GSE securitized mortgages.

To recap: If private-sector loans performed far worse than loans touched by the government, how could the GSEs have led the race to the bottom?”

…

Indeed, the SEC lawsuit specifically says Fannie and Freddie began to do more risky business not to meet their goals, but rather to recapture market share – and they began to do so aggressively in 2006, when the market was already peaking. So while the GSEs played a huge role in blowing the bubble bigger than it otherwise would have been – and the numbers in the SEC complaint are huge – they followed, rather than led, the private market.

It’s also very hard to look at what happened in the crisis and conclude that nothing went wrong in the private sector. Note that the other Republican members of the FCIC refused to sign on to Wallison’s dissent. Instead, they issued their own dissent. “Single-source explanations,” they said, were “too simplistic.”

Yet despite all that, the one-note Republican refrain hasn’t changed. The explanation is obvious: The “government sucks” rant polls well with conservatives. Mix in an urge to counter the equally simplistic story from the left – that the crisis was entirely the fault of greedy, unscrupulous bankers – and you get a strong resistance to the facts. Maybe there’s a deeper reason, too. For many, belief in the all-knowing market was (and is) almost a religion. This financial crisis challenged that faith by showing the market would indeed allow loans to be made that could never be paid back, and by showing that highly paid financial services executives aren’t gods, and that many of them are stupid and venal and all too human.

So maybe the Republican orthodoxy is understandable, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t scary. Of course, there’s the great line from Edmund Burke: “Those who do not know history are destined to repeat it.” Our housing market is a mess that threatens to drag down the entire economy, and whoever is president in 2013 needs to have a plan. Denying the facts is not a good start.

The Republicans that dissented blamed the whole crisis on the government and the private (GAO – “Inasmuch as the GSEs are already privately owned, it seems odd to speak of privatization as a policy option.”) GSEs (which they want to think of as “government” – GSEs ).

The government cannot tell the GSEs what to do. HUD can make requests as Bush did…

As the Washington Post article states,

“But by 2004, when HUD next revised the goals, Freddie and Fannie’s purchases of subprime-backed securities had risen tenfold. Foreclosure rates also were rising.

That year, President Bush’s HUD ratcheted up the main affordable-housing goal over the next four years, from 50 percent to 56 percent. John C. Weicher, then an assistant HUD secretary, said the institutions lagged behind even the private market and “must do more.””

Bush did not want to put Fannie and Freddie under government control, the FHFA (H.R. 1461). This is why he said in the statement below, “In order for a financial regulator to be respected and credible, it must have the authority and ability to adjust capital requirements of the institutions it oversees as circumstances dictate to ensure prudential operations. Given the size and importance of the GSEs, Congress must ensure that their large mortgage portfolios do not place the U.S. financial system at risk.” He thought the FHFA would “divert profits will lead to increased risk-taking and decreased market discipline, while exacerbating systemic risk”. He also stated in the policy below, “Instead, provisions of H.R. 1461 that expand mortgage purchasing authority would lessen the housing GSEs’ commitment to low-income homebuyers.”

If you read the history of this you will find Bush wanted it under Treasury control. He thought FHFA was incompetent but the Treasury department could handle the job. He had more influence through the Treasury Department.

“Statement of Administration Policy”

October 26, 2005

“The Administration has long called for legislation to create a stronger, more effective regulatory regime to improve oversight of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks (“housing government-sponsored enterprises” or “housing GSEs”) and appreciates the considerable efforts of Chairman Oxley and Chairman Baker in crafting H.R. 1461. However, H.R. 1461 fails to include key elements that are essential to protect the safety and soundness of the housing finance system and the broader financial system at large. As a result, the Administration opposes the bill.

The regulatory regime envisioned by H.R. 1461 is considerably weaker than that which governs other large, complex financial institutions. This regime is of particular concern given that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac currently hold only about half of the capital of comparable financial institutions. In order for a financial regulator to be respected and credible, it must have the authority and ability to adjust capital requirements of the institutions it oversees as circumstances dictate to ensure prudential operations. An effective oversight regime must also provide for clear review of business activities to ensure the integrity of the housing finance system and consistency with the GSEs’ housing mission. The Administration does not believe that the housing GSEs should be exempt from these important standards of world-class regulation.

…

The Administration strongly believes that the housing GSEs should be focused on their core housing mission, particularly with respect to low-income Americans and first-time homebuyers. Instead, provisions of H.R. 1461 that expand mortgage purchasing authority would lessen the housing GSEs’ commitment to low-income homebuyers. Likewise, provisions that divert profits will lead to increased risk-taking and decreased market discipline, while exacerbating systemic risk.

Here is a note about types of mortgages:

The overall conventional mortgage market (nongovernment insured or guaranteed) is comprised of two broad categories of loans, prime and subprime. Prime mortgages constitute the largest category, representing loans to borrowers with what lenders regard as good credit (“A” quality, or investment grade). Everything else is subprime – loans to borrowers who have a history of credit problems, insufficient credit history, or nontraditional credit sources. Subprime mortgages are rated by their perceived risk, from the least risky to the greatest risk: A-minus, B, C, and even D. However, A-minus loans account for 50 to 60 percent of the entire subprime market.

http://www.nhi.org/online/issues/125/goingsubprime.html

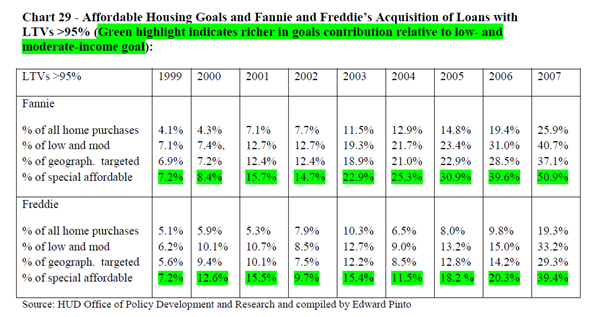

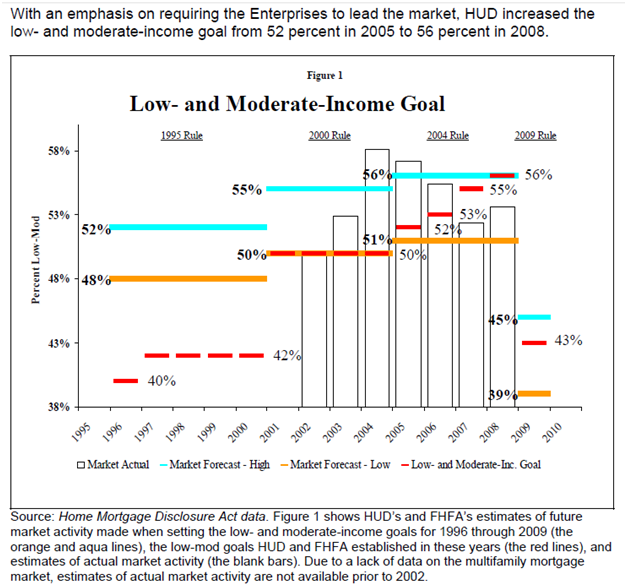

As you can see below the Bush administration viz. HUD urged the GSEs to set these goals:

From Pinto’s report:

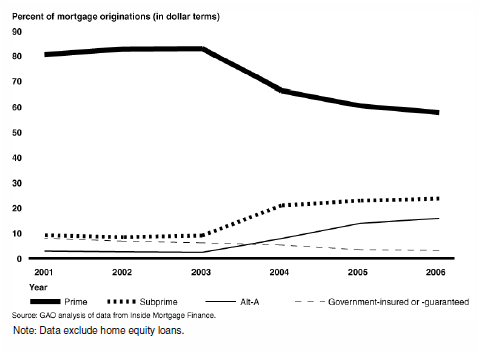

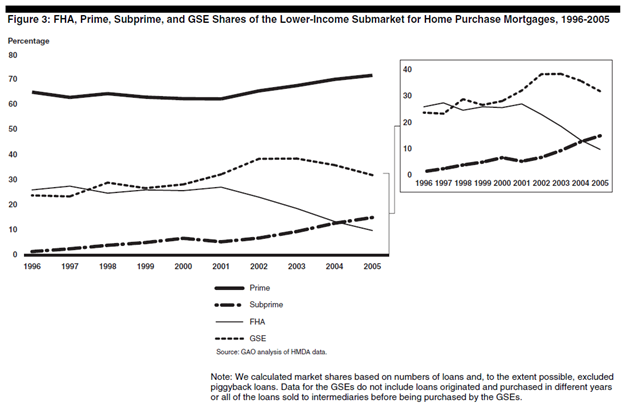

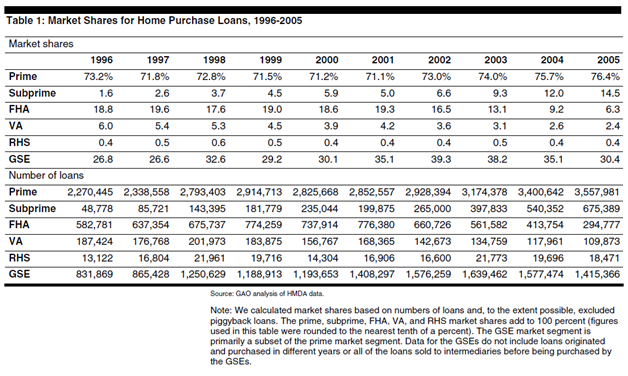

This is what the market did according to the GAO (Note: These sources are not from the GSEs):

Historical Chart of the Total Mortgage Market (Note: For the rest of the charts FHA and VA loans are “Government-insured or –guaranteed”). This data comes from the Mortgage Bankers Association’s (MBA) quarterly National Delinquency Survey (NDS). It shows the total mortgage data from 2001 to 2006.

Note: “The housing goal oversight function was transferred to the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) on July 30, 2008, with the enactment of the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA).”

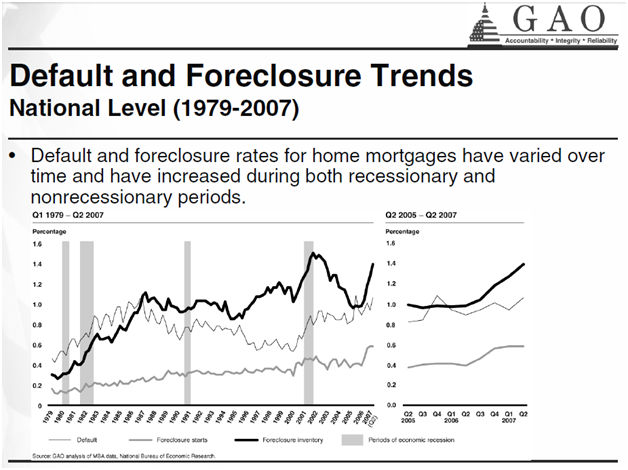

This is total market default and foreclosure rates.

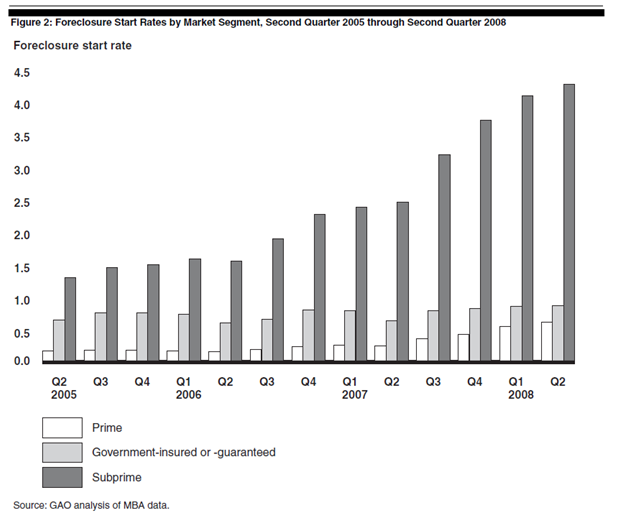

This is total market foreclosure start rates.

This is total mortgage market share.

This is total mortgage market share.

These GAO charts and graphs show that the total default rates and foreclosures are much closer the FCIC findings than the dissents of Wallison and Pinto’s report.

http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d09231t.pdf

http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d0878r.pdf

Here are some other articles and quotes on the crisis:

http://economics-the-economy.factoidz.com/what-caused-the-great-recession-of-20082009/

http://economics-the-economy.factoidz.com/what-caused-the-great-recession-of-20082009/

“Greenspan replied that the institutions subject to the Federal Reserve’s or other federal-banking regulators were not the primary players in the subprime-loan origination business.

“The data show that, in 2004 and 2005, more than half of subprime loans were originated by independent mortgage companies subject to consumer-protection enforcement by the Federal Trade Commission and various state agencies,” he said.”

Here is another article:

“The notion that the federal government, via the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and by pushing housing finance giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to meet affordable housing goals, was responsible for the financial crisis has become Republican orthodoxy. This contention got a boost from a recent lawsuit the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filed against six former executives at Fannie and Freddie, including two former CEOs. “Today’s announcement by the SEC proves what I have been saying all along—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac played a leading role in the 2008 financial collapse that wreaked havoc on the U.S. economy,” said Congressman Scott Garrett, the New Jersey Republican who is chairman of the financial services subcommittee on capital markets and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs).

But the SEC’s case doesn’t prove anything of the sort, and in fact, the theory that the GSEs are to blame for the crisis has been thoroughly discredited, again and again. The roots of this canard lie in an opposition—one that festered over decades—to the growing power of Fannie Mae, in particular, and its smaller sibling, Freddie Mac. This stance was both right and brave, and was mostly taken by a few Republicans and free-market economists—although even President Clinton’s Treasury Department took on Fannie and Freddie in the late 1990s. The funny thing, though, is that the complaint back then wasn’t that Fannie and Freddie were making housing too affordable. It was that their government-subsidized profits were accruing to private shareholders (correct), that they had far too much leverage (correct), that they posed a risk to taxpayers (correct), and what they did to make housing affordable didn’t justify the massive benefits they got from the government (also correct!). Indeed, in a 2004 book that recommended privatizing Fannie and Freddie, one of its authors, Peter Wallison, wrote, “Study after study has shown that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, despite full-throated claims about trillion-dollar commitments and the like, have failed to lead the private market in assisting the development and financing of affordable housing.”

When the bubble burst in the fall of 2008, Republicans immediately pinned the blame on Fannie and Freddie. John McCain, then running for president, called the companies “the match that started this forest fire.” This narrative picked up momentum when Wallison joined forces with Ed Pinto, Fannie’s chief credit officer until the late 1980s. According to Pinto’s research, at the time the market cratered, 27 million loans—half of all U.S. mortgages—were subprime. Of these, Pinto calculated that over 70 percent were touched by Fannie and Freddie—which took on that risk in order to satisfy their government-imposed affordable housing goals—or by some other government agency, or had been made by a large bank that was subject to the CRA. “Thus it is clear where the demand for these deficient mortgages came from,” Wallison wrote in a recent op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, which has enthusiastically pushed this point of view in its editorial section since the crisis erupted.

But Pinto’s numbers don’t hold up. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC)—Wallison was one of its 10 commissioners— met with Pinto and analyzed his numbers, and concluded that while Fannie and Freddie played a role in the crisis and were deeply problematic institutions, they “were not a primary cause.” (Wallison issued a dissent.) The FCIC argued that Pinto overstated the number of risky loans, and as David Min, the associate director for financial markets policy at the Center for American Progress, has noted, Pinto’s number is far bigger than that of others—the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office estimated that from 2000 to 2007, there were only 14.5 million total nonprime loans originated; by the end of 2009, there were just 4.59 million such loans outstanding.

The disparity stems from the fact that Pinto defines risky loans far more broadly than most experts do. Min points out that the delinquency rates on what Pinto calls subprime are actually closer to prime loans than to real subprime loans. For instance, Pinto assumes that all loans made to people with credit scores below 660 were risky. But Fannie- and Freddie-backed loans in this category performed far better than the loans securitized by Wall Street. Data compiled by the FCIC for a subset of borrowers with scores below 660 shows that by the end of 2008, 6.2 percent of those GSE mortgages were seriously delinquent, versus 28.3 percent of non-GSE securitized mortgages.

To recap: If private-sector loans performed far worse than loans touched by the government, how could the GSEs have led the race to the bottom?

Another problematic aspect to Pinto’s research is that he assumes the GSEs guaranteed risky loans solely to satisfy affordable housing goals. But many of the guaranteed loans didn’t qualify for affordable housing credits. The GSEs did all this business because they were losing market share to Wall Street—their share went from 57 percent in 2003 to 37 percent by 2006. As the housing bubble grew larger, they wanted to recapture their share and boost their profits.

Indeed, the SEC lawsuit specifically says Fannie and Freddie began to do more risky business not to meet their goals, but rather to recapture market share—and they began to do so aggressively in 2006, when the market was already peaking. So while the GSEs played a huge role in blowing the bubble bigger than it otherwise would have been—and the numbers in the SEC complaint are huge—they followed, rather than led, the private market.

It’s also very hard to look at what happened in the crisis and conclude that nothing went wrong in the private sector. Note that the other Republican members of the FCIC refused to sign on to Wallison’s dissent. Instead, they issued their own dissent. “Single-source explanations,” they said, were “too simplistic.”

Yet despite all that, the one-note Republican refrain hasn’t changed. The explanation is obvious: The “government sucks” rant polls well with conservatives. Mix in an urge to counter the equally simplistic story from the left—that the crisis was entirely the fault of greedy, unscrupulous bankers—and you get a strong resistance to the facts. Maybe there’s a deeper reason, too. For many, belief in the all-knowing market was (and is) almost a religion. This financial crisis challenged that faith by showing the market would indeed allow loans to be made that could never be paid back, and by showing that highly paid financial services executives aren’t gods, and that many of them are stupid and venal and all too human.

So maybe the Republican orthodoxy is understandable, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t scary. Of course, there’s the great line from Edmund Burke: “Those who do not know history are destined to repeat it.” Our housing market is a mess that threatens to drag down the entire economy, and whoever is president in 2013 needs to have a plan. Denying the facts is not a good start.”

http://blogs.reuters.com/bethany-mclean/2012/01/25/faith-based-economic-theory/

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/bernanke20100902a.htm

http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/speeches/chairman/spjan1410.html

“In particular, the authors accuse two quasi-public but profit-making companies, Fannie Mae (the Federal National Mortgage Association) and Freddie Mac (the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation), of adding risks to the mortgage markets that resulted in disaster. Much the same criticism has been made by Peter Wallison, a fellow of the American Enterprise Institute, who wrote an angry dissent to the findings of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC), which was appointed by Congress to investigate the causes of the crash. Contrary to Wallison, the nine other members of the commission, including three others appointed by Republicans, concluded that Fannie and Freddie were not the main causes of the crisis.

The GSEs did buy subprime mortgages in the 2000s, but contrary to the impression given by Morgenson and Rosner, their purchases were always a distinct minority of those sold by Wall Street. As Jason Thomas and Robert Van Order of George Washington University further point out, the subprimes the GSEs bought in these years were from the safer triple-A tranches of basic mortgage-backed securities, i.e., the highest quality of groups of mortgages rated by their risk of default. The GSEs never bought the far riskier collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) that were also rated triple-A and were the main source of the financial crisis. (The triple-A classifications of some of those CDOs were conferred on them very dubiously by the credit-rating agencies, Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s.) It turned out that subprimes accounted for only 5 percent of the GSEs’ ultimate losses, according to Thomas and Van Order.”

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/oct/27/did-fannie-cause-disaster/?pagination=false

Here are some articles on derivatives and credit default swaps:

http://politicalcorrection.org/factcheck/201101280003

“Credit default swaps are not standardized instruments. In fact, they technically aren’t true securities in the classic sense of the word in that they’re not transparent, aren’t traded on any exchange, aren’t subject to present securities laws, and aren’t regulated. They are, however, at risk – all $62 trillion (the best guess by the ISDA) of them.

Fundamentally, this kind of derivative serves a real purpose – as a hedging device. The actual holders, or creditors, of outstanding corporate or sovereign loans and bonds might seek insurance to guarantee that the debts they are owed are repaid. That’s the economic purpose of insurance.

What happened, however, is that risk speculators who wanted exposure to certain asset classes, various bonds and loans, or security pools such as residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities (yes, those same subprime mortgage-backed securities that you’ve been reading about), but didn’t actually own the underlying credits, now had a means by which to speculate on them.

If you think XYZ Corp. is in trouble, and won’t be able to pay back its bondholders, you can speculate by buying, and paying premiums for, credit default swaps on their bonds, which will pay you the full face amount of the bonds if they do actually default. If, on the other hand, you think that XYZ Corp. is doing just fine, and its bonds are as good as gold, you can offer insurance to a fellow speculator, who holds the opinion opposite yours. That means you’d essentially be speculating that the bonds would not default. You’re hoping that you’ll collect, and keep, all the premiums, and never have to pay off on the insurance. It’s pure speculation.

Credit default swaps are not unlike me being able to insure your house, not with you, but with someone else entirely not connected to your house, so that if your house is washed away in the next hurricane I get paid its value. I’m speculating on an event. I’m making a bet.

The bad news is that there are even worse bets out there. There are credit default swaps written on subprime mortgage securities. It’s bad enough that these subprime mortgage pools that banks, investment banks, insurance companies, hedge funds and others bought were over-rated and ended up falling precipitously in value as foreclosures mounted on the underlying mortgages in the pools.

What’s even worse, however, is that speculators sold and bought trillions of dollars of insurance that these pools would, or wouldn’t, default! The sellers of this insurance (AIG is one example) are getting killed as defaults continue to rise with no end in sight.

What is happening in both the stock and credit markets is a direct result of what’s playing out in the CDS market. The Fed could not let Bear Stearns enter bankruptcy because – and only because – the trillions of dollars of credit default swaps on its books would be wiped out. All the banks and institutions that had insurance written by Bear would not be able to say that they were insured or hedged anymore and they would have to write-down billions and billions of dollars in losses that they’ve been carrying at higher values because they could say that they were insured for those losses.

The counterparty risk that all Bear’s trading partners were exposed to was so far and wide, and so deep, that if Bear was to enter bankruptcy it would take years to sort out the risk and losses. That was an untenable option.

The Fed had to bail out Bear Stearns.

The same thing has just happened to AIG. Make no mistake about it, there’s nothing wrong with AIG’s insurance subsidiaries – absolutely nothing. In fact, the Fed just made the best trade in its history by bailing AIG out and getting equity, warrants and charging the insurance giant seven points over the benchmark London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) on that $85 billion loan!

What happened to AIG is simple: AIG got greedy. AIG, as of June 30, had written $441 billion worth of swaps on corporate bonds, and worse, mortgage-backed securities. As the value of these insured-referenced entities fell, AIG had massive write-downs and additionally had to post more collateral. And when its ratings were downgraded on Monday evening, the company had to post even more collateral, which it didn’t have.

In short, what happened in one small AIG corporate subsidiary blew apart the largest insurance company in the world.

But there’s more – a lot more. These instruments are causing many of the massive write-downs at banks, investment banks and insurance companies. Knowing what all this means for hedge funds, the credit markets and the stock market is the key to understanding where this might end and how.

The rest of the story will be illuminated in the next two installments. Next up: An examination of the AIG collapse, followed by a look at how bad things could get, and what we can do to fix the problem at hand. So stay tuned.

[Editor’s Note: Contributing Editor R. Shah Gilani has toiled in the trading pits in Chicago, run trading desks in New York, operated as a broker/dealer and managed everything from hedge funds to currency accounts. In his new column, “Inside Wall Street,” Gilani promises to take readers on a journey through the “shadowy back alleys” of the U.S. capital markets – and to conduct us past the “velvet rope” that guards Wall Street’s most-valuable secrets – in an ongoing search for the investment ideas with the biggest profit potential. If the whipsaw markets we’re experiencing lead to the so-called market “Super Crash” that many analysts fear, shrewd investors won’t have to worry. The reason: They will be able to capitalize on the once-in-a-lifetime profit plays that we detail in a new report. For a copy of that report – which includes a free copy of CNBC analyst Peter D. Schiff’s New York Times best-seller, “Crash Proof: How to Profit from the Coming Economic Collapse” – please click here.]

Part 1

http://moneymorning.com/2008/09/18/credit-default-swaps/

Part II

http://moneymorning.com/2008/09/22/credit-default-swaps-2/

Part III

“That’s where the magic of financial engineering, better known as structuring, comes into play. I can divide up the closed pool of subprime mortgages and structure the pool into layers, or tranches. What I’ll do is divide up the pool into multiple tranches, or slices. I’ll structure the cash flow payments from all the mortgages so that if the 1st or 2nd tranches run into trouble, I’ll take cash flow payments from the lower tranches to keep up with all the payments to the holders of the 1st and 2nd tranches.

For someone trying to peddle these asset-backed securities, this is a stroke of genius. In our example, since I’m now pretty much guaranteeing that the 1st and 2nd tranche security holders are going to get paid, maybe I can get the Big Three debt-rating companies – Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s Investors Service (MCO) and Fitch Ratings Inc. – to give my 1st and 2nd tranche CDOs’ investment grade ratings. Maybe I can even buy insurance from a monoline insurer like AMBAC Financial Group Inc. (ABK) or MBIA Inc. (MBIA), and get my top tranches a coveted “AAA” rating. Wow, I could sure sell a lot of this high-yielding stuff with an investment grade rating”

http://moneymorning.com/2008/09/24/financial-meltdown/

http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2008/10/17/600-000-000-000-000.html

The following chart shows HUD goals for the percent of GSE business.

http://www.fhfa.gov/webfiles/15408/Housing%20Goals%201996-2009%2002-01.pdf.pdf