This is the next part in a series on the Austrian school of economics. The previous parts were here and here.

On regulation Jonathan Catalan states:

In the United States, for example, anti-branching laws and growing restrictions on note-issuing, such as taxes on certain banks’ notes, made it increasingly difficult to respond to information runs caused by inflationary episodes also stimulated by government intervention: namely, the circulation of greenbacks between 1862–71, issued to pay for the American Civil War and the resulting debt, and later fiduciary over-issue encouraged by allowing national banks to issue notes backed by government bonds and the manipulation of the exchange value of gold and silver. Eventually, runs and consequent panics, especially that of 1907, led to the formation of the Federal Reserve System. This did little to constrain banks and actually intensified fiduciary over-expansion, ultimately leading to the Great Depression and the creation of deposit insurance.

So restrictions on note-issuing “made it increasingly difficult to respond to information runs caused by inflationary episodes also stimulated by government intervention”. It is hard to tell from this whether Catalan is in favor of local banks issuing notes but it does appear as if he is not in favor of restrictions on note-issuing. I would wonder, if he is in favor of unrestricted noted issuing by local banks, if he would also favor a reserve requirement on these notes. It would seem that anything less than a 100% reserve requirement would constitute a kind of money creation and thereby allow local banks to loan money they do not have.

However, it would seem that Catalan is not in favor of any reserve requirement regulations when he states:

Also popular are capital controls, which are intended to force banks to hold a certain volume of their own capital against their investments. This is what the three Basel frameworks are, in part, intended to do; in the United States, prior to the 2010 adoption of a framework based on Basel III, these efforts were mimicked by the recourse rule. Different assets were rated against their perceived market risks and then organized into buckets and tranches. Ideally, the riskier the asset the more capital banks have to hold against it. In the event of the liquidation of an investment the bank can partially patch the loss with the reserve.

These regulations have not passed the test.

In any case, the loaned money would not come from ‘savings’ but would constitute an “an artificial increase in loanable funds” by the local bank (see this). The artificial increase in loanable funds would have nothing to do with a central bank. The question that arises is why this artificial increase, originated from a local bank, would have different effect on the cost of capital goods for production and the decision process made be entrepreneurs than the artificial increase made by government owned central banks. Wouldn’t the entrepreneurs still be lulled into a false sense of security from the availability of loanable funds regardless of whether it came from local banks or central banks? It seems this specific dynamic would not be affected by the source of the funds. However, the argument could be made that the local banker would be more discretionary about lending if the banker’s created funds were not covered from a lower interest rate loan from the central bank system. The reasoning would be that if the local bankers risk rested solely on his lending decisions then he would be much less likely to make ill-informed loans.

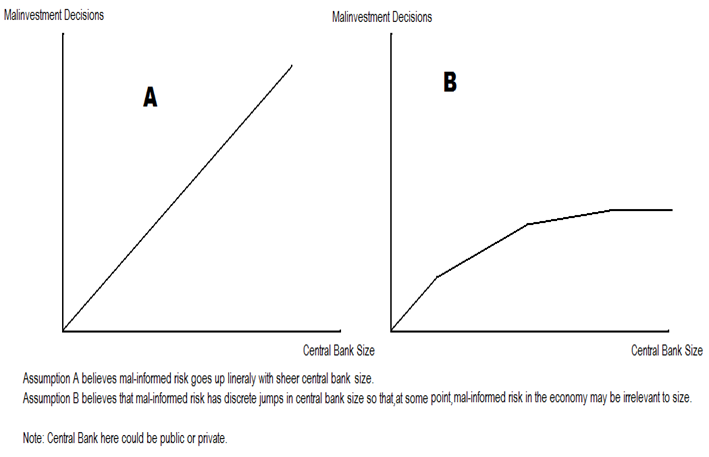

It is interesting that in view of putting the sole risk for the investment decision on the local banker, Catalan would also appear to favor pulling restrictions on bank branching. When banks branch they are owned and operated from a central, corporate agency. They relinquish sole local control of banking decisions with more or less degrees to their corporate owners. The effect of this is to offset risk to the corporate owners, the central bank. At this point we are faced with the question of why the corporate owners of local banks would have a different effect on the dynamic of local bank investment decisions than a government controlled central bank. Perhaps the argument would be made that the government controlled central bank would exercise orders of magnitude more of the de-localized effect on investment banking than the corporate owned central bank. However, if there are no regulations on how large a corporate owned bank could be as the Austrians would certainly favor, the free market ‘faith’ in competition would be the only limiting factor on corporate owned, centralized banks. One problem with this ‘faith’ is the monopoly dynamics that I previously point out in this series. However, another problem rests on a mathematical assumption. If the government controlled central bank is assumed to be much larger than the corporate owned bank then, it is assumed, that the risk off-load by more centralizing is also linear correlated to the absolute size of the central bank. However, it may be that the relationship is not linear at all. It may be that there are discrete jumps in failed risk assessments on the part of bankers in a privately owned corporate bank that make absolute size differences in the government owned central bank and the corporate owned central bank inconsequential.

Another assumption is that the scope of the malinvestment decisions will have a random distribution pattern over the entire market so that bad individual decisions will have a minimum effect on the whole economy. I will reiterate the pointed I made here:

Additionally, institutional investors do not invest equally and randomly over the entire breadth of the market. Institutional investors invest more heavily in businesses and market segments with proven track records. This has a congealing effect on capital investments in less risky, more certain returns on investment. To the degree that this occurs larger businesses with larger capital resources become the instrument of new business start ups and venture capital gets diverted from unaffiliated [with larger corporations] start ups to market conglomeration dynamics. This natural pocketing of capital resists the notion that a randomized investment pattern offsets risks/loses in the market and therefore exercises the least possible negative effects on individual parts of the market making booms and busts not likely [or less likely] to occur. It is quite possible that because of market conglomeration and even more, market monopolizing, that apart from central banking concerns, booms and busts would still occur and their impact might not be mediated by the idealized, random effects of the pure free market, the fundamentalist’s dream.

These issues cannot just go away by Austrian economists wishing them away. The only way to really resolve them would be with empirical data.

Catalan goes on to state:

Deposit insurance takes the place of market processes that accomplish much of the same thing, but by externalizing the burden of failure to the taxpayer. Deposit insurance, much like last resort lending without ex ante restrictions, causes problems of its own. It eliminates the need for market discipline, or constraints placed upon banks by its clients and investors, because these people are essentially insured against the loss of their deposits. Banks are given leeway to make what are perceived to be riskier investments, and regulators soon saw the need to step in to guard against excessive risk-taking by these regulated financial institutions.

This is an astonishing claim. What this claim fails to recognize is that the individual depositor has no role in that actual investment decision the bank makes. If the banker makes the wrong decision and the depositor losses all his deposit, the banker may learn a free market lesson but the banker has learned the lesson at the cost of the depositor not at the bankers own personal cost. Yes, you could say that the depositor has also learned a free market lesson, not to use that bank. However, the lesson the depositor has learned has come at the cost of his entire deposit so he could make a better decision next time if only he had any money to learn it with. The banker could lose his business if he makes many such bad decisions but he has made a good salary and bonuses in the meantime. The free market lesson the depositor has learned has come at a much higher real cost than the free market lesson the banker has learned. It is an equivocation to make all ‘lessons’ equal by virtue of the free market. The difference in these ‘lessons’ was recognized by the creators of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. They also recognized that when masses of depositors called consumers ‘learn the lesson’ in this fashion the economy tanks.

Finally, Catalan states:

Financial entrepreneurs, however, enjoy a crucial advantage over regulators — they are constrained by the market process. The world is replete with people looking to make a profit, as such there is no shortage of potential bankers. Those who make bad decisions suffer losses and are forced off the market; profits, on the other hand, reward good results. The phenomenon of profit and loss is an essential market process that continuously redistributes capital to those who best use it. This is the “market discipline” that early interventions did so well to marginalize.

Here, the free market ‘faith’ of the fundamentalist is most apparent. This is why I started this series highlighting the guiding philosophy of the Austrian economist rather than merely dealing with specific problems. It is assumed here that the financial entrepreneurs learn their lessons and are forced out by “market discipline”. I wonder if Catalan would acknowledge the possibility that the financial entrepreneurs might learn another free market lesson. Perhaps they will learn that if at first they do not succeed in making a 10 million dollar bonus, only of a 5 million dollar bonus, try, try again. To hope that the bad financial entrepreneurs will get redistributed out of the market without any access to capital may happen at times but it may also be that other factors such as the good old boy network may exert a stronger influence on job security. Even if the bad financial entrepreneur is forced out, the sheer size of his bonuses and salaries relative to other free market laborers may not have the same equivalent affect as other laborers that lose all their depository funds with no other financial recourse. The bad financial entrepreneur has no need of insurance against loss because his loss is only a dip in net personal gain whereas the consumer that deposits all their savings in a depository account and had no role in the bad financial entrepreneur’s investment decisions has only his next paycheck (if there is one) to bank on. There is an inequity in loss here that is ignored and ‘believed’ away by the fundamentalist. When the depositors in the Great Depression lost their faith they did not continue to consume they quit consuming and the deflation that resulted took ten years to recover from. Do the Austrians really want us to try it again to see if it works this time? Not all of us have that much faith.

Note: There is a pattern of continual deferral in this fundamentalist thinking that validates the entire free market process by the ongoing deferral itself. The process itself is thought to be a randomized, distribution that is self-correcting. For example, the free market lesson learned by the manufacturing entrepreneur is passed on to the financial entrepreneur. The financial entrepreneur’s lesson is passed on to the bankers. The banker’s lesson is passed on to the depositor and consumer. The consumer’s lesson is passed on to the manufacturing entrepreneur in terms of consumption and thus, a repetitive singularity occurs that is ‘believed’ to be self-correcting. In other forms of science a singularity in calculations is bad science but I suppose in Austrian economics the singularity is deemed as the self-correcting success of the system. This process is purely abstract in that it thinks losses as lessons and self-correction. It fails to take into account or even allow failures in the system as legitimate, proper failures of the system itself and defers the failures to illegitimate, improper interventions in the system. Thus, it rightly achieves the title of ‘fundamentalism’.