This is an ongoing conversation I have been having with a Hegelian. I think it is interesting and informative. Antonio seems like a really sharp young person. He has taught a old dog like me a few things about Hegel so who says and old dog can’t learn new tricks. …still have major misgivings with Hegel…

His blog is here: The Empyrean Trail

He has also published on some other sites.

To skip ahead to the latest comments look for “***New Comments***” towards the bottom of this post.

***Previous Comments***

Me…

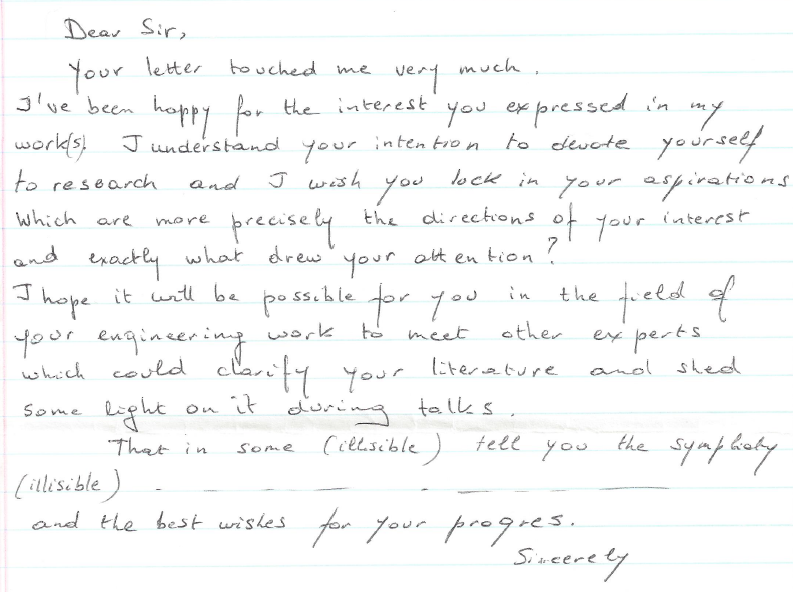

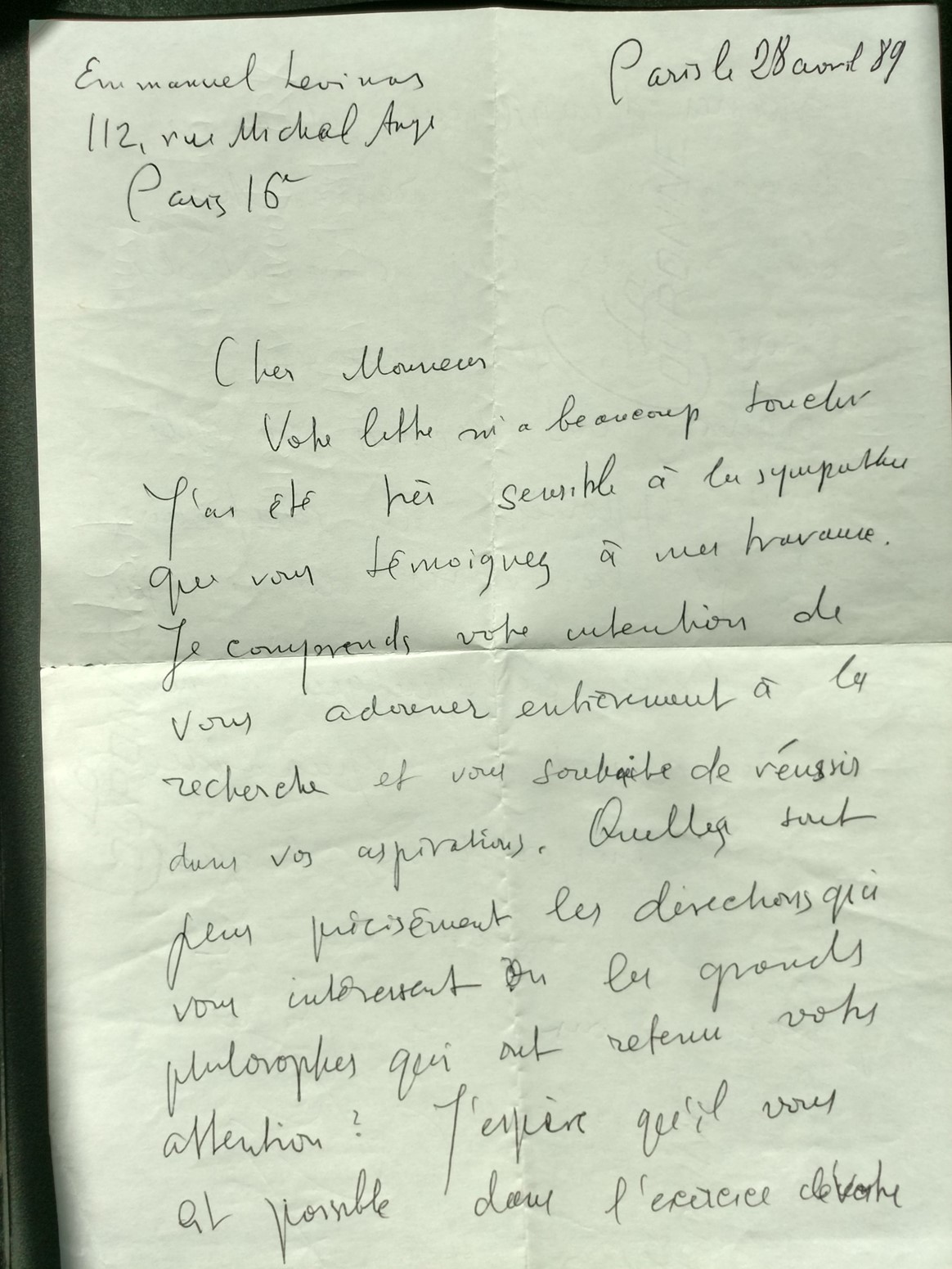

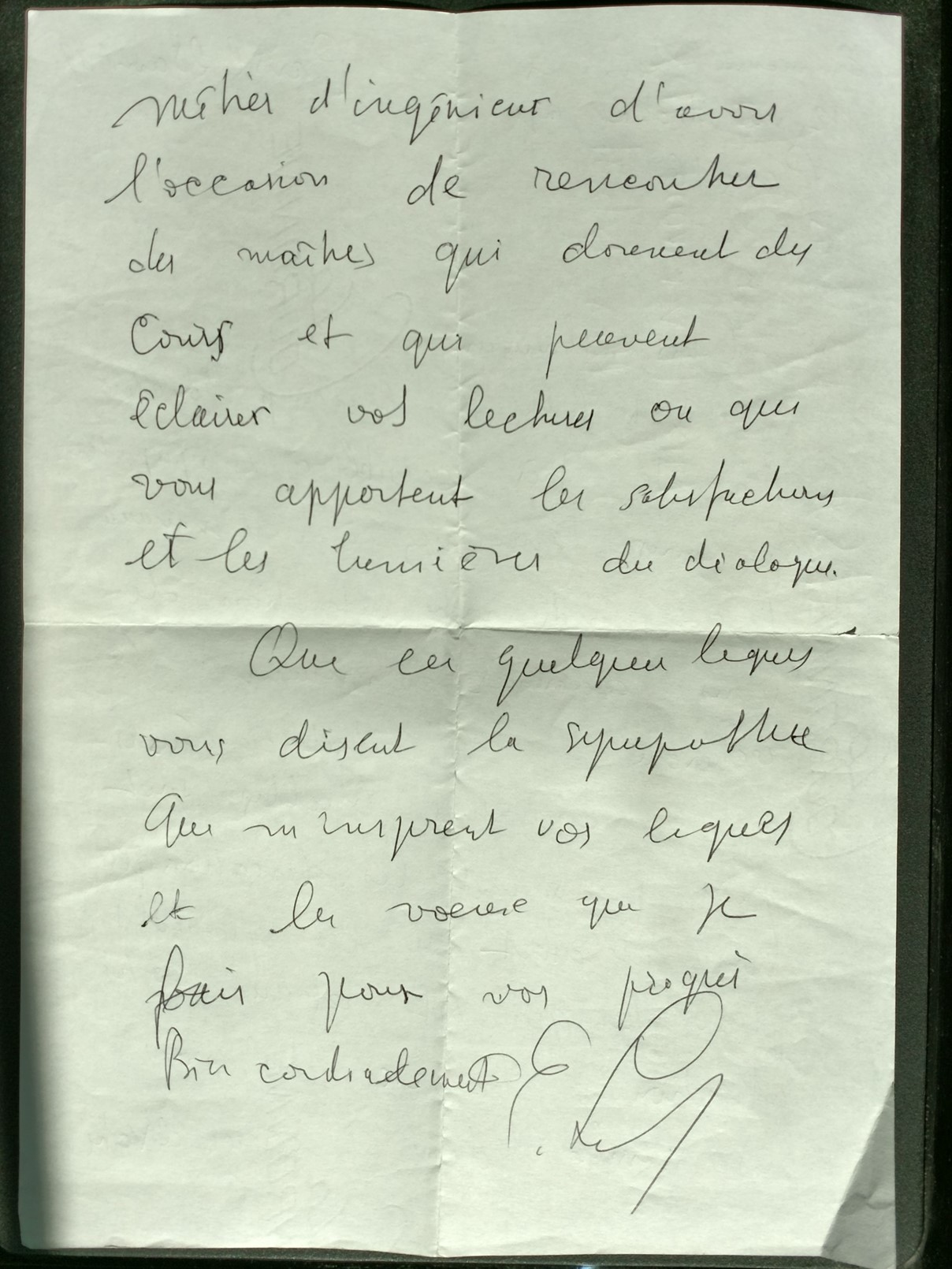

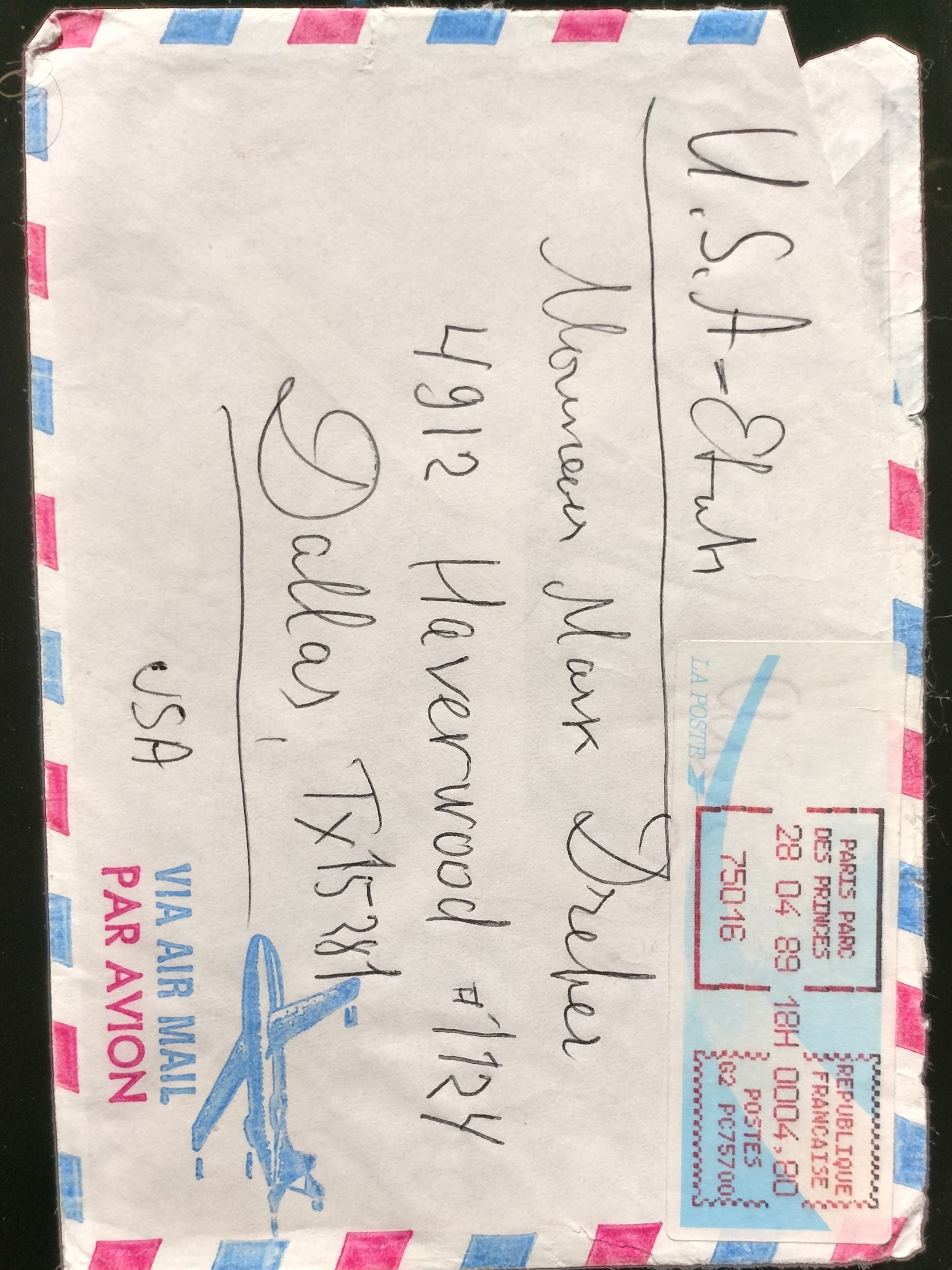

Hello. I am also an amateur student of philosophy. I did three graduate programs officially in philosophy and audited other programs while working professionally as an engineer. My background is ancient Greek philosophy and contemporary continental philosophy (Heidegger, Derrida, Levinas, Husserl, Hegel, …). Here are some of my questions concerning this article:In general, it seems like a pattern that Hegel’s dialectic starts with pure indeterminateness and emptiness, abstraction, pure knowing, – then, negates such to give way a more positive, determinate which then, gives way to aufhebung which holds both together in their mutual self-negation as lifted up and transformed into a more concrete Idea. I am thinking of:

Being->Non Being->Becoming, the One->the Many->Repulsion->Attraction->Quantity

Being-in-itself->Being-for-other->Limit->Finite->Infinite

Essential->Unessential->pure mediation-Being’s pure immediacy->Reflection->External

Reflection->Determining Reflection->Identity->Difference->Contradiction->Ground

All have these dynamics play with terms such as abstraction, emptiness, negation otherness -> to/from -> opposition, positive otherness -> aufhebung

Hegel seems to think these dynamics prevent his Idea from being susceptible to the tautologies or ordinary science. Tautologies in this sense seems to simply be naming something then repeating the definition in the ‘findings’ of science. This seems to be a naïve view of science (especially for the “Encyclopedia of Science”) in that science is pervaded with supposition->empiricism->contradiction-> paradigm transformation. Certainly, ‘empiricism’ can be deemed a metaphysic, an abstraction, a tautology, etc. but it could also simply be a pragmatic assumption which allows further inquiry. Any Concept or Idea has, at least, this pragmatic, functional capacity including Hegel’s terms like Being, Otherness, Negation, Contradiction, etc. In a minimal sense what I have referred to as the dynamic, pragmatic terms, for Hegel indeterminate, abstraction, emptiness, negation, otherness, aufhebung, etc., are not unlike mathematical operators such as addition, division, square root, etc. in that they reflect relationships. Hegel seems to think he ends up in absolute Concept, Idea and completes philosophy as the System. It seems to me his Ideas are more reflective of a Newtonian styled absoluteness (i.e., time and space) than the newer sciences of relativity, quantum uncertainty, observer effect, dark matter and energy, etc.. – Indeterminacy in the newer sciences is not swallowed up as an artifact of dialectic but would remain in the same apotheosis as absolute Idea or Concept for Hegel.

The other or otherness is always peppered in as idea. To ‘think’ of the other as a he or a she would be what for Hegel? A he or she is yet another concept or idea that faces us? Would a ‘real’ he or she be a metaphysic? Would it simply be yet another form of the depraved naturalism of science? A he or she ‘in time’ even as the idea of a he or she assumes time and the ‘thought’ of a he or she.

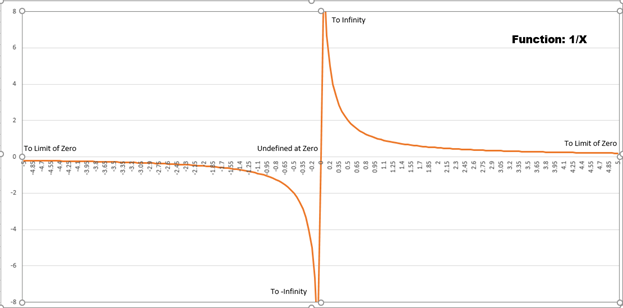

What is to ‘think’? Doesn’t it assume time (e.g., a specific thought or thought process). Let’s look at Hegel’s notion of time:

Shall we say the ‘In the beginning was the Concept’, could we say time-space-less-ness? Concept is NOT the thought yet or the word (logos) – assumes time.

The absolute other of time is pure, empty, indeterminate space without dimensions of course.

The absolute other of space is a point.

The absolute other of the abstract point turns out to be time…which turns out to be yet another empty abstraction moving towards past, present, future, etc..

Ok, let’s ‘think’ about this…The Concept is concrete self-determinateness as Idea. We have not asserted any ‘thing’ yet (perhaps literally). Anyway, Concept must have an absolute other which is space. But space is also an idea – not empirical or any such metaphysic, so how can ‘space’ be an absolute other in the ‘absolute’ sense. Sure, it can be a contradictory idea or shall we say the ‘anti’ of tautology, tautology being Concept as Idea. Why do I write ‘tautology?

The jump from Idea to space (which turns out to be yet another idea) is not so complete as Hegel would have us believe. Anyway, from there we go to the point and then temporality. So thinking happens in time but Idea has not yet developed the notion of time so thinking (e.g. about Concept) cannot happen in time since Concept is time-space-less-ness. Yet, do we assume concept is something absolutely other from thinking? How can we think that without ‘thinking that’? Are we now postulating some kind of transcendent other (i.e., the Idea without thinking) – have we not lapsed into metaphysics but deny ourselves the possibility of thinking Idea as such? Wouldn’t this metaphysical leap be the hobgoblin of all self-respecting post-post-post (ad infinitum)-modernists. Hegelians tell us they are not metaphysicians – yet if Idea talks like a duck, quacks like a duck, waddles like a duck…isn’t it a duck? If Concept can be thought without thinking it haven’t we simply asserted yet another tautology?…otherwise called a metaphysic. Could it be in the highly circuitous route we have taken to Concept we have conveniently lost the notion of ‘metaphysic’ even though the dynamic Idea without a thought harkens back to God without Being and convinced ourselves that it is surely and essentially different?

———————————————————————————

Antonio…

Concerning Hegel’s critique of empirical science I can see why you would think this, but Hegel’s critique of science is actually simpler and rather a critique of what goes on in the Phenomenology in a pointed sense. The main argument is about his concept of theory and practice, and he does have a rather short version of it in the Introduction to the Phil of Nat. The critique of theory attacks both rationalist and empiricist doctrines of science, and something like pragmatism is for Hegel just not worthy of attack since it has given up the attempt of science as absolute knowledge.

Concerning empiricism as a metaphysical doctrine, well, in Hegel’s concept of metaphysics it is. All concepts of ontological nature are at once both about what is and how to know it. The way we think of the world is a metaphysics. I agree, and Hegel would too, that his concepts are indeed exactly what you describe as mathematical functions, which is why concepts are logics. I would say, however, that it is a mistake to term Hegel’s views as grounded on a Newtonian view of absolutes (Hegel despises Newton, just as an aside) since how Hegel conceives things is not what anyone even today conceives as an absolute *even* at the radical process fringes of QM and related theories. As someone most simpathetic to the critics of modern science, *especially physics*, I would say that one must be careful with the dogmatic adoption of these new terms about reality, particularly due to their nebulous indeterminacy and a historical lineage of conception by contingent caprice and erroneous hand-waving of things ‘out of fashion’ such as a demand for coherency and intelligibility. History tells us much of the origin of these terms, and they are indeed not entirely pragmatic but rather a necessity of axiomatic dogmatism taken for fact.

Concerning otherness and the “he/she” and what concerns the thinking of such. At an ontological level, this ‘thinking’ manifests as the action of a ‘he/she’ and their relating to us. In this it is what they are and thus, yes, a metaphysic.

Concerning the he/she in time, it seems you really wanted to get at the existential presupposition of time in regarding the pure logic of self-thinking thought. Concerning beginnings, well, Hegel denies there ever was a beginning since everything in the finite sphere has a prior and posterior without end. Concerning the relation of time and space: you must keep in mind that Hegel’s foundational structure and dynamic of all Nature is self-externality. Depending on how we will look at this externality, either as substance or subject, being or activity, we shall determine this self-externality as space or time. The otherness of time and space is based on the unifying role of this self-externality such that space qua space finds itself existent through the diremption that is time, and time qua time finds itself existent through the diremption that is space.

Expanding on how “space” can be the absolute other of the Concept, I’m not going to pretend I fully know Hegel’s explanation for this, however, there are a few simple structural reasons that can be given. For one, the determination of the Logic in its closure of the Absolute Idea is the determination of logic as a domain of self-thinking thought. Experience, however, tells us there is more than pure thought, there is a realm of out-there-ness we call Nature. If logic qua logic is determinate, it exists, therefore it is determinately negated, therefore it has an other, this other is the Idea opposing itself, hence outside itself, and this relation is its fundamental concept: self-externality. There is the simpler and more straight forward logical explanation, which is that logic being determinate and existent now moves towards an opposite domain which is by negation determinate as not-logic, not self-immanent thought, but the inverse, and this is fittingly called Nature.

As for Hegel being a metaphysician: He does not deny it, I don’t deny it, but by his conception of metaphysician literally everyone who has a thought about any fundamental aspect of reality, cognitive or substantive, is engaging in the act of metaphysical determination of their world by positing some view as the true absolute (even relativism cannot escape this).

Returning to the problem of existential presupposition of the Concept: yes, *we* must and do think temporally in a natural sense. The conception of pure logic, however, is not about a temporal thinking, but just the process of the self-determination of thought, a determination that has always already been complete with all its defined parts. An atom’s self-determination certainly does not await time for its complete determination, even in frozen space it is logically articulated in many ways in one single moment. The determination of time is irrelevant for logic as such, and if you are pragmatic, you know this is the case for the world itself. Removing time cannot and does not remove at least half of the determinations of things, mostly the substance portion of logic, but plenty of dynamic logic still remains even without time (conditionality, relations, etc).

This blog is unfortunately in need of a deep revising which I have worked on over time. Currently the draft stands at double the length and certain sections like the one on time have been significantly changed in an attempt to clarify, as well as my comments on science in general have expanded to try to show the concreteness and relevance to issues today. I don’t find much to disagree with Hegel here in this first chapter, but trust me, I know I have differences with him which are indeed to do with the advances in knowledge we have had.

Thank you for your comment, I appreciate that others read

these monstrosities I write haha.

———————————————————————————

Me…

Metaphysics was a term applied to a collection of Aristotle’s works in the first century AD. It has been entangled in Latin and Catholic interpretations which as Heidegger thought obscured more than clarified Aristotle’s works. Aristotle described his subject matter as ‘first philosophy’ or the study of being as being. I have written on my blog rather extensively about the earliest form, phusis (φῠ́ω thought to be from proto-indo-european (phúō, “grow”) + -σῐς (-sis)), which pervaded ancient Greek thought from Heraclitus and Parmenides. From the earliest, phusis is a kind vitalism which increasingly through ancient Greek thought takes on the budding rationalism of logos. For Aristotle, Metaphysics was a survey concerned with ‘first cause’ and the origin of things. It was the highest level of generalization. However, Metaphysics from Latin Neoplatonism and Christian thought transformed and lost some of the earliest origins of phusis. Metaphysics became a leap, a dogmatism, which equated being with God, God beyond being, and eventually base metal with gold vis-à-vis the philosopher’s stone, etc.. My impression is that for Hegel after Kant the metaphysical would always be fashioned in purely negative terms since it is impossible to determine if synthetic, a priori claims are ‘absolutely’ true. Metaphysical dogmatism was discredited by Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason. However, the ‘thing-in-itself’ was precisely what Hegel wanted clear up and do away with from Kant. Beiser thinks Hegel resists using the term Metaphysics except in a negative sense of the pre-Kantian, rationalist tradition. In any case, Beiser certainly argued that Hegel retained a pre-Kantian foundationalist approach that the absolute could be obtained through reason – “What is rational is real; And what is real is rational.”. In this way, Hegel seems to retain an influence form Spinoza albeit in the idealistic tradition. It seems that many contemporary philosophers do not find a transcendental leap of faith in Hegel but a highly rational and analytic approach to the absolute which was not typical of many of the traditional domains of metaphysicians.

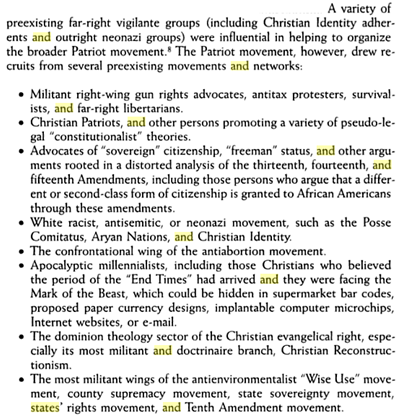

The dogmatism you referred to in your reply and the ‘not’ of Hegel’s ‘metaphysics’, in your opinion, was certainly something Hegel thought he overcame. Certainly, indeterminacy and uncertainty are not hallmarks of traditional dogmatism which insists on the opposite, determinacy and certainty. I am not a pragmatist but I do take pragmatism as a starting point at times for the least possible and most commonly accessible starting place for agreement on terms. If indeterminacy and uncertainty have become a modern form of ‘scientific’ dogmatism that is news to me. My engineering background and further education in relativity and quantum mechanics do not play loosely with those terms. However, when I look in my own philosophical background for scientific equivalents I am not faced with Hegelian certainties and rationalism. Certainly, we know that Hegel’s earlier attempts with the ether did not end so well. I would also argue that his totalitarian and authoritarian views on how more enlightened cultures were allowed, entitled by right, to handle the more primitive cultures strikes a negative and violent tone to his absolute certainties (which I consider dogmas i.e., not ‘proven’ by his dialectics as he thinks). Because the state is divine freedom is defined as right, violence is given necessary and free reign as “Machiavellian genius” (Hegel’s opinion of Machiavellian – “the great and true conception of a real political genius with the highest and noblest purpose”). Violence can only come to its end after it has had its ‘last word’ and the last word has been accepted as divine. As Nietzsche tells us, history is the story told by the victors. Hegel certainly used the Christian motif in his terminology and the kenosis of Jesus. For Hegel, God may be the whole or Spirit and certainly has a historical relationship to Christianity. In any case, it has a double play which intentionally plays on historical Christianity and rationalism. In this double play I see a intentional indeterminacy which can also lead to “a necessity of axiomatic dogmatism taken for fact”. Uncertainty and indeterminism always plays an inferior role in Hegel’s dialectics. That is, they are certainly never in themselves. They are always an avenue, a vehicle, which never ‘stand-in-themselves’. They always ‘stand-for-another’. Indeterminacy and uncertainty lead us to determinacy and certainty – to the rational, the logos. I do think in spite of Hegel’s dislike for Newton he did favor a “Newtonian styled” orientation at the very least, in a reductionary pragmatic sense, in the fact that both of them highly favored the ‘absolute’. Also, both of them favored notions of Christianity and God although I will give you for very different rationales.

Let’s take a specific case in the start of Hegel’s Logic – of Being he tells us:

“Being, pure being, without any further determination. In its indeterminate immediacy it is equal only to itself. It is also not unequal relatively to an other; it has no diversity within itself nor any with a reference outwards. It would not be held fast in its purity if it contained any determination or content which could be distinguished in it or by which it could be distinguished from an other. It is pure indeterminateness and emptiness. There is nothing to be intuited in it, if one can speak here of intuiting; or, it is only this pure intuiting itself. Just as little is anything to be thought in it, or it is equally only this empty thinking. Being, the indeterminate immediate, is in fact nothing, and neither more nor less than nothing.”

of nothing he tells us:

“Nothing, pure nothing: it is simply equality with itself, complete emptiness, absence of all determination and content — undifferentiatedness in itself. In so far as intuiting or thinking can be mentioned here, it counts as a distinction whether something or nothing is intuited or thought. To intuit or think nothing has, therefore, a meaning; both are distinguished and thus nothing is (exists) in our intuiting or thinking; or rather it is empty intuition and thought itself, and the same empty intuition or thought as pure being. Nothing is, therefore, the same determination, or rather absence of determination, and thus altogether the same as, pure being.”

Let’s symbolize this as Being = A, Nothing = B, indeterminate, immediacy = C

A = C

B = C

Therefore: A = B or Being is Nothing

Then we have Becoming…

“Pure Being and pure nothing are, therefore, the same. What is the truth is neither being nor nothing, but that being — does not pass over but has passed over — into nothing, and nothing into being. But it is equally true that they are not undistinguished from each other, that, on the contrary, they are not the same, that they are absolutely distinct, and yet that they are unseparated and inseparable and that each immediately vanishes in its opposite. Their truth is therefore, this movement of the immediate vanishing of the one into the other: becoming, a movement in which both are distinguished, but by a difference which has equally immediately resolved itself.”

Here Hegel tells us that actually Being and nothing does have a determination in spite of the fact the he just told us both are absolutely and immediately indeterminate (and therefore the same). He told us that Being and nothing are the same and now he tells that they are not the same. Now we find out that they have a distinction – a determinacy. In either case, Being or Nothing, they are still that same as immediacy. So while they do and do not have determinacy (i.e., they are absolutely distinct), they both have immediacy. Each one immediately vanishes into the other. So now we have a difference even though they are the same. The difference and their immediate nullity is becoming. Moreover, becoming is mediation.

So now we have determinacy (i.e., they are absolutely distinct) and mediation = D

Certainly, we can say that C != D (where != is not equal). They are actually syllogistically, diametrical opposites.

Now Hegel wants to say A = C = D and B = C = D

Therefore: A = B or Being is Nothing but here we have absolutely contradicted ourselves because C != D

So, we have contradicted ourselves. Is Hegel telling us that the contradiction is becoming and therefore we now have:

Being = Nothing = absolute indetermination and absolute immediacy = determination (absolutely distinct) and mediation (since they are both held in their absolute contradiction (both the same and different)

As far as I can see the only way to maintain this as TRUE is not based on logical deduction from a necessarily TRUE categorical syllogism but to maintain it dogmatically (and falsely) as a tautology. It is not really a tautology but it is assumed by Hegel to be necessarily and absolutely TRUE and as a categorical syllogism BUT it cannot be proven true with a common medium term only a common medium contradiction (which must be ‘intuited’ and lifted up). Additionally, in Kant’s term the beginning of “The Logic” cannot be analytic, a priori and thus necessarily true but can only be a synthetic judgement in that terms are applied to the subjects (Being and nothing) which are not contained in the mutual and contradictory predicates (indeterminate, immediacy, determinate, mediate). Synthetic judgements are always contingent on perception. Contingency does not belong to the absolute in Hegel. Are we to arrive at the absolute when we start with the contingent? Certainly this is a question of are synthetic a priori judgements possible? I think they are. The may or may not be true but there can never be an ‘absolute’ truth as analytic, a priori judgements. They can never obtain that level of absolute if you will. If you add in intuition, conditioned by categories of sensibility by Kant, you can arrive at a contingent certainty (such as cause and effect appears in empirical observation) but those judgements are ALWAYS conditioned by a degree of indeterminacy and uncertainty.

If we are now to

apply intuition to Hegel’s Logic (i.e., we intuitively know that Being is

distinct from nothing) we have introduced another medium term from ‘Being =

indeterminate, immediacy = nothing’ to ‘Being = indeterminate, immediacy =

determinate, mediate = nothing’. The

start in Hegel’s logic begins in intuition and therefore contingency and ends

in Concept – the ‘absolute’ (not contingent).

Haven’t we made base metal into gold?

Are we to assume that the philosopher’s stone will resolve our dilemma?

———————————————————————————

Antonio…

Regarding the definition of metaphysics, well, I place no value on it whatsoever. Frankly, I don’t care if someone is or is not metaphysical according to anyone. Hegel talks about metaphysics both as that generality of Being and Essence, but also as ontology in general which ends up making all philosophy nothing but a metaphysical exercise in asserting anything fundamental in any categorial sense. Whether you, Heidegger, or anyone else agrees I see as having no concern *within* Hegelianism. The issue with using someone else, even Kant, to define Hegel and point out strange contradictions is precisely that Hegel himself doesn’t *take* definitions from anyone, and his concepts are themselves not definitions in a common sense either. While one may talk about the relation, as Hegel himself does, one has to keep in mind Hegel conceives the relation not of himself to them, but them to him once he has his systematic groundwork in place. In this same way, although here I admit total immanent ignorance, charges of ‘onto-theology’ against Hegel strike me as, well, rather inane from a Hegelian standpoint itself. I’ve seen descriptions of this concept and have been given some by some self-professed Heideggerians and I always found it a strange charge (there have been times when a couple Hegelians reverse the charge against Heidegger lol on related matters such as the ontic difference).

Being, thought, and God aren’t exactly the same thing for Hegel except for the implicated dynamic that binds everything as the Absolute. The unity of Being and thought is, I think, a rather clever conception made by Hegel on analogical ground (Phenomenology of Spirit Preface) of existence=abstraction=thought, as well as the simple conceptual ground (Logic): With the concept of Being the only existential possibility is nothing due precisely to its immediacy.

Concerning the Absolute, while Newton was an absolutist, I think it mistaken if not disingenuous to equate what these two refer to by the same term name. Hegel’s absolute is not something else different and independent of the relative like Newton’s absolute space and aether were in regard to motion. The relative is not relative as something else, but as a moment which depends yet also is depended on for the realization of the Absolute.

Concerning Hegel’s politics, I certainly won’t defend his outlooks. First, because I’m not yet familiar with the works in their proper logic, and second because even if I was I am not someone who will defend Hegel for being Hegel, he does indeed have failures in lapses of his own methodology. However, as someone with some eye towards history, may I say that a Machiavellian prince is certainly something that for all realities of our nice natures does seem to be a great necessity in maintaining a shift from one social world to another. To my mind comes Simon Bolivar, whose liberal kindness and resolute moral idealism unfortunately ended up betraying his own dream and that of the continent he helped liberate… all because he refused to be a dictator in a historical moment where such concentration of power and vision was required to see the project of a new Latin America through. Poor fool. As for Hegel’s totalitarian tendency, well, I think that’s overstating things considering the whole of the project is to see the freedom of individuality flourish, which of course requires the stability of its social totality. Take my point with a grain of salt, however, I don’t speak for Hegel or Hegelians here, it’s so far an opinion based on a singular view of history.

Regarding the Being, Nothing, Becoming issue. You’re right to note that there is something glaring in the claims and methodology, but Hegel himself tells us so right from the first pages of that chapter. The beginning, as he presents it, is a ruse. He begins legitimately, but explains the movement in illegitimate form in taking on our own assumptions of the nature of these distinctions (hence the identity through indeterminacy/indifference and difference through intent). First is the intent, second is of course the appeal in Nothing to *existence* in order to make the return to Being. A lot of this issue sort of arises not just because these term names have some implication of some pretended meaning that seems unutterable, but that immediacy itself really is weird to us who are so determinate and used to given determinateness.

The issue of this beginning is that it is so abstract that linguistically there is simply going to be an inescapable failure to describe the immanent move without relying on external categories. Discounting the intention of meaning, we can make the difference of Being and Nothing in many ways: form and content, appearance and essence, thought and thinking. The beginning is presuppositionless and indeterminate in its *immanent intelligibility*. Indeed, these concepts don’t presuppose other concepts, they are what we conceive normally as closest to pure immediacies. In being truly immediate, they cannot be relative in the sense of Being vs Nothing, because that would presuppose the relation. Though thought content in conceptual form is indeterminate, we cannot escape that thinking is inescapably determining in action and determinate as existent. Regardless of how we try to explicate these categories, however, their indeterminacy only transfers to everything else if we try to be immanent, and though we may do things determinately we are left incapable of saying anything immanently as to why these are determinate.

The truth of the distinction, as I see it, is simply that we *can* make the distinction in act despite not having any conceptual cognizance of how we can conceive that we did it. This is because thinking is a capacity/power capable of self-abstraction without any seeming limit (its reflexivity). Thinking can think of thinking, and the fundamental split at the beginning is simply two faces of the thought process itself: thought and thinking. We are either immersed in penetrating thought already, or we are standing back from thought prior to this immersion. Being is thought, Nothing is thinking. We either notice the immediacy in its form/thought and simply determine that it is present indeterminately, or we notice the immediacy in its content/thinking which re-emerges into thought as the recollection of this activity and the observation that presence was absent in the engagement. With this there is no appeal to some intent to Being or Nothing, nor is their identity through a third, but rather through their inverting reflexion: Being is Nothing because that is what its thinking reveals itself to be. Nothing is Being because that is what its thought reveals it to be. Here, of course, you may charge that intention has only shifted to the subjectivity of attention—we want to attend to something different about each—and thinking of it right now, you may be right, but I have quite a bit of thinking I’ve been doing on this particular formulation of it and it still needs development. Part of me hopes that maybe this formulation has something more objective due to its tie to the nature of thought itself, of course, a nature which is not internally conceivable at the beginning.

Here, of course, you may level against Hegel the charge that indeed he is wrong or lying about his supposedly logical methodology because he *indeed has relied on an intuition*. This charge, I think, Hegel would simply wipe off like a chip on his shoulder. The intuition here is not at all a sensuous intuition. It is from the beginning an intellectual intuition about what thinking experiences of itself in pure thought terms, for it is indeed as I call it a phenomeno-logic that Hegel uses the entire way across all works from the beginning. Thinking itself has a phenomenal being, and why shouldn’t it? The appeal to the empty intuition of Nothing can indeed be taken in sensuous form, that of the suspension of thinking simply temporally idling with no possible engagement. We can, however, just as well recognize this as something we may want to call intellectual intuition of this suspension of thinking itself: immediate thinking is immediately negated, halted—absent. To call this an intuition in any Kantian sense is of course erroneous, and Hegel himself doesn’t use such language, but if we may speak of experience as learning, and if thought is an object of thinking, thinking intuits thought in a loose sense. If you find this unappealing, it can just as well be cast off as a rather sloppy description in terms, but what Hegel does remains working just as well.

I don’t in any way expect this satisfies your curiosity and answers its problematic, but rest assured I too am (when I get into the issue) puzzled by the enigmatic beginning of the Logic as well.

Finally, to return to something earlier, on your mention of empirical science, pragmatism, and its concepts (such as indeterminacy), I’m not quite sure what you mean without any determinate (ha) case for you to give. I don’t think it would at all be fair to say that, say, the concept of indeterminacy in QM is what Hegel would be referring to by his concept of indeterminacy.

All in all, thanks a lot for the email. I would offer some books to read… but I don’t actually read many about Hegelianism so I can’t. I certainly enjoy a challenge, and if I seem stubbornly Hegelian it is perhaps because I am. My mind is thoroughly determined in the Hegelian conceptual fashion which is certainly quite different to what you’re used to, and I can say the same to the Heideggerian logic which is unusual to me. I’m only familiar with small bits of Heidegger, but those small bits are actually ones I like quite a lot due to how well thought they are, and how they meld well with Hegelian thinking. I’m afraid I ramble now.

———————————————————————————

Me…

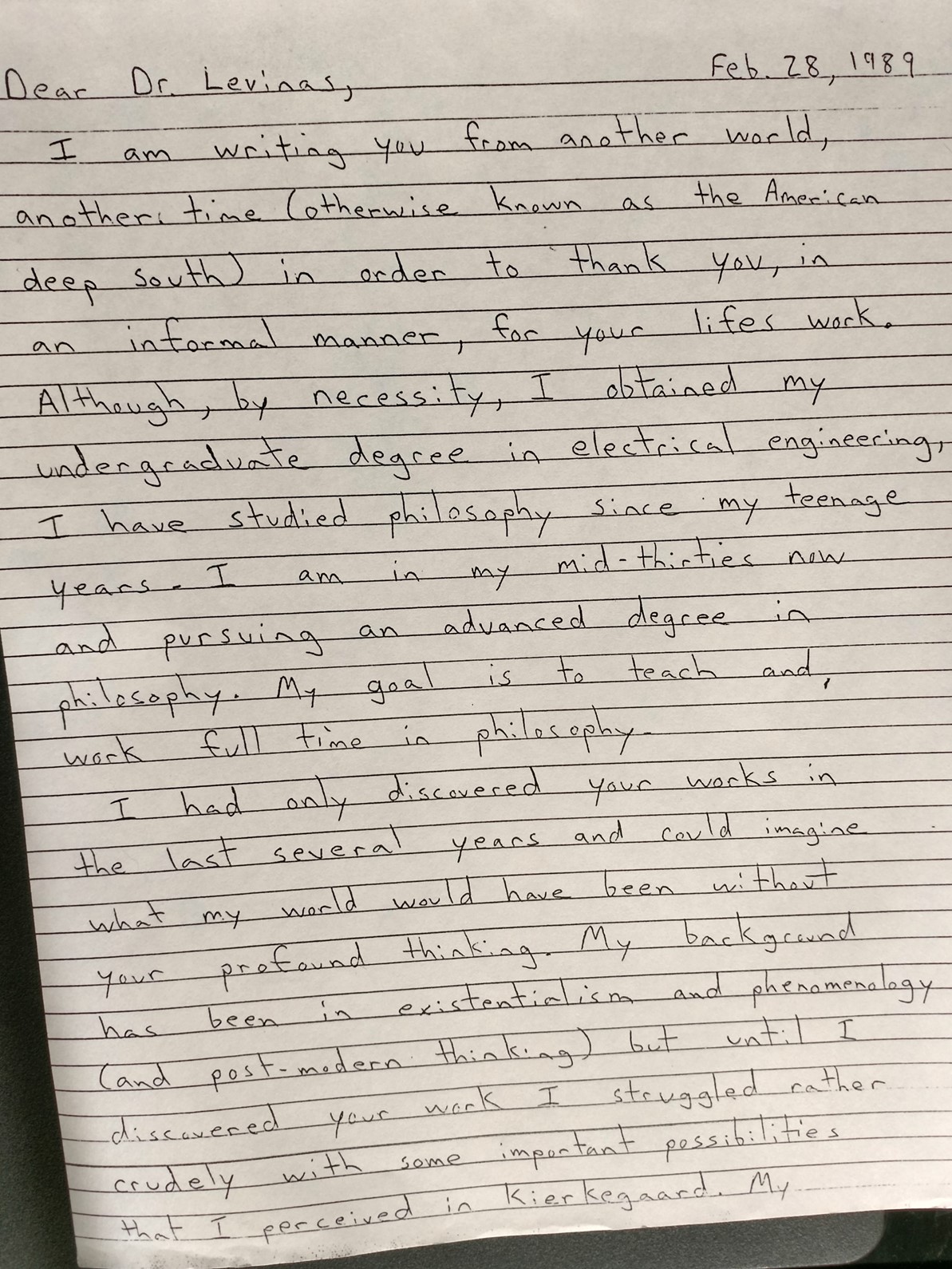

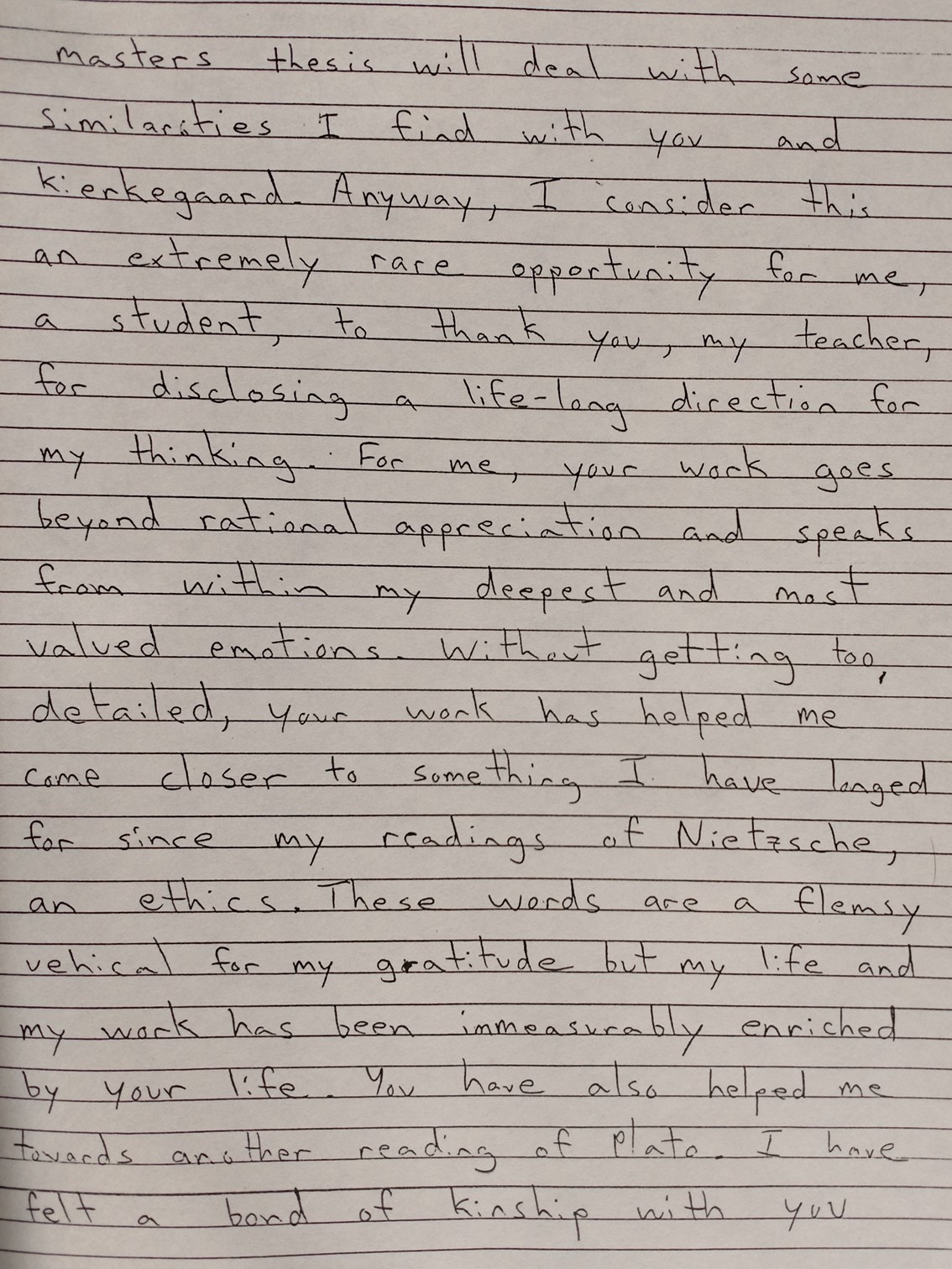

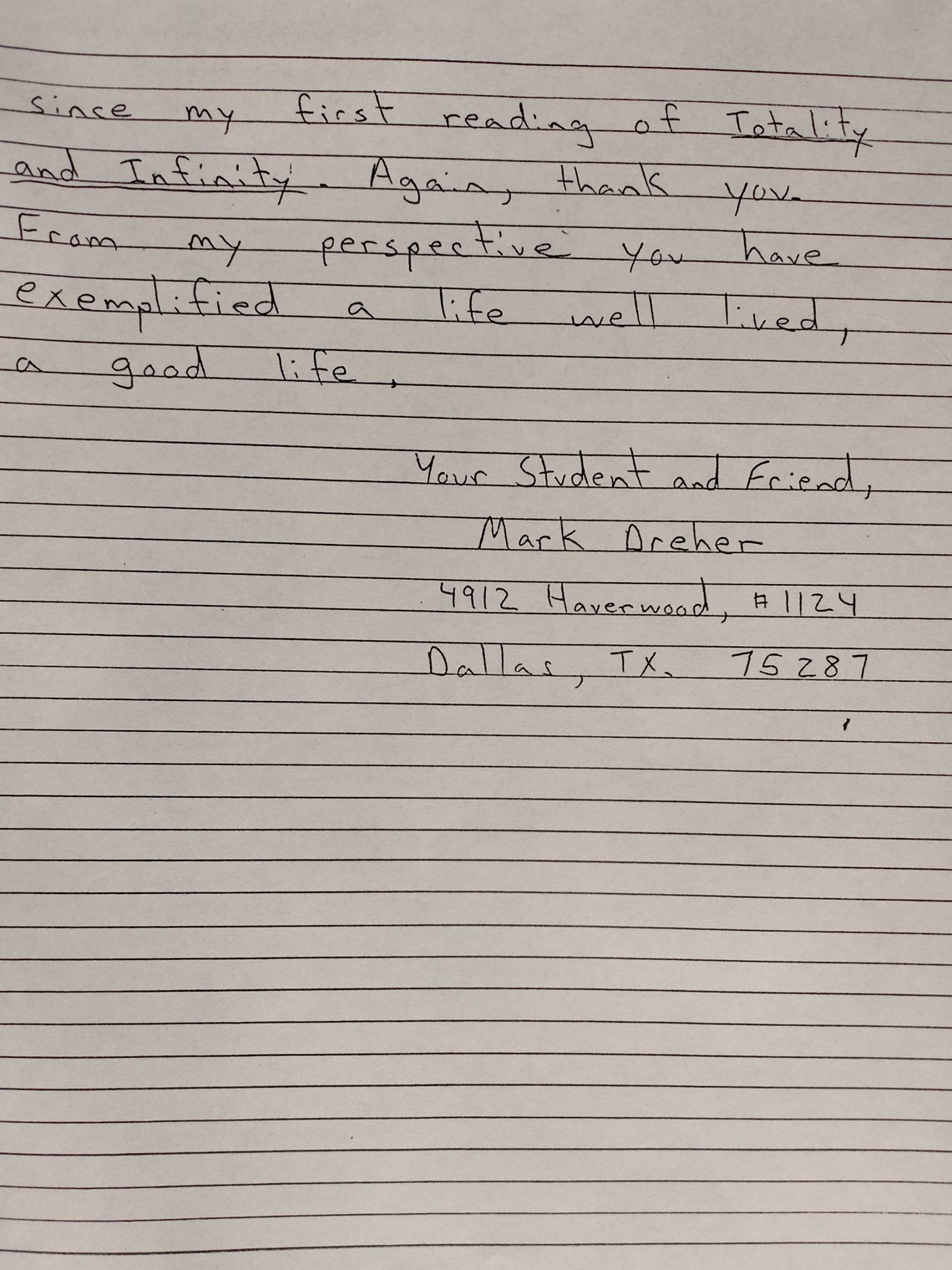

First, I am flattered a Hegelian would even take the time to talk to me. The academics I have known including my best friend for decades will not engage in this kind of conversation at all. To be fair, they spend all their time ‘publishing or perishing’. I can tell you have not had a wide variety of exposure to philosophical thinkers but that is ok – I think philosophy should be fair game for all no matter what their background. I can also tell you are a very bright young (I think) person and quite impressive for your Herculean efforts in what is probably the most difficult philosopher to understand. I also like you honesty in dealing with the material. From a very young age to the age of 62 (and having retired at the age of 43) I have had a lot of time for academic and my own studies in philosophy. I have a broad background in the history of continental philosophy (not so much analytic tradition) with an emphasis in the ancient Greeks and contemporary philosophy (starting at the beginning of the 20th century). I have had a number of decades in philosophy but still a content beginner IMO.

You are right in detecting that much of my academic background was in Heidegger. However, for a number of years now I have not considered myself to be a Heideggerian. I understand Heidegger now as having more to do with German Idealism than I previously thought. More generally, my background in contemporary philosophy has been in phenomenology which is not the ‘phenomenology’ of Hegel but starting with Husserl. This phenomenology was about not abstracting away from phenomena but observing it as it shows itself in such phenomena as lived time – the stretch of subjective time, epochs for Heidegger et al, etc. (not abstract linear ‘now’ moment time – oh, lived time fits well with relativity – came about around the same time) or lived space – as regions of deseverance for a subject, horizons for history and language, etc. (not abstract geometrical three dimensional space – fits well with QM).

Perhaps my critical concern of ‘metaphysics’ comes from my reading of post-modernists, Derrida in particular. His critique of ‘logocentrism’ certainly plays into the history of violence (capitalism, Stalinism, etc.). He brings out the dogmatism in metaphysics not with another dogma but with a deconstruction of the text…using the margins of the text…the text’s own implicit determinations to undermine its ‘canon’. I have read and talked to Hegelians which I think come from contemporary Hegelianism that believe Hegel is NOT metaphysical in essence. They think that his logic follows rationally, immanently, without any transcendental leaps into metaphysics. I know there have been many schools of Hegel which differ from that orientation and are more sympathetic to your irrelevance of the term.

In any case, I would currently think of myself as a Levinasian (he has been called an anarchist communist). He was a student of Heidegger and Husserl but went in very different, and I would say very conflictive, directions from Heidegger. For Levinas, simply put, the history of violence which he also finds in German Idealism is a history of retreat from the face of the other. The face of the other is an infinity, a radical alterity which ontology retreats from. Levinas’ major later work is entitled “Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence”. Levinas reserves the absolute as the he or the she which faces me and breaks through the ‘plastic cast’ I form of them given by the history of totality. The other is not Concept or Idea but face that confounds me. History which is the effacement of the other is ontology. From this relation you can see how Levinas derives an ‘Ethics’ not as an altruism, a derived duty or idea, but a primacy from the ‘anarchic’ start with the encounter of the other. The other has a ‘time not my time’ a ‘past not my past’ which cannot be coincident with my phenomenal temporality. He calls this a ‘diachrony’. All of our historic, linguistic categories which synchronizes time/space, universalizes idea, gives us certainty and determinacy (i.e., ‘reality’, being, Concept, even historic metaphysics, etc.) have been derived from an absolute inability to face the infinity of the other – a ‘passivity beyond all passivity’. Before we think we are held captive by a substitution – I for the other.

In any case, I like the openness towards the other I find in Levinas. I see a violence and reductive immanence in universalizing idea, naturalism (materialism, positivism, pragmatism, etc.)…a totality which truncates and essentially alienates. Levinas as many of the other contemporary phenomenologists starts in embodiment, lived sensibility, etc. and even his Ethics is from the ‘touch’ not the Idea of the encounter with the other.

I know this is off the topic but I did want to give you a little background on where I am coming from so you do not have to guess. I, as I think for yourself, am left of liberal and an activist for many years. I also like Marx – his critiques of capitalism in particular). I guess I would be more of the Trotsky type in that I take Marx to be speaking of a natural ‘evolution’ towards socialism and, for him ultimately, communism. If nothing else, with the advent of technology and manufacturing automation, the future cannot be pure capitalism unless we are willing to exterminate the masses so only the elite can thrive. We will have to think productivity and value in very different terms in the future than pure, Austrian capitalism can conceive.

I still love philosophy as Levinas did – incredible scholar. I am intrigued by Hegel and the absolute ‘idea’-lism which for me, personally would be an absolute horror and false security that would reduce all to the one, the Idea, and forgo any excess – to the point of annihilating something phenomenally essential to ‘otherness’. If ‘otherness’ is the occasion for dialectic culminating in self-determining Concept, certainly the protests of existentialism (Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, etc.) go unheeded but beyond that any ‘other’ has already been determined in advance as Idea (for Hegel). I also have seen in Hegel and his students an indifference (perhaps smugness) and arrogance about his ‘presumption-less’ philosophy. I and many others do not accept that on face value. I think it is an exaggeration and apothotheois which cannot stand up to critical examination.

Notwithstanding my critical concerns of Hegel, I will say that I do have admiration for him. He obviously had an incredible mind – even the very fact that he is sooo hard to criticize says something about his genius that few philosophers have ever attained. I can see his philosophy as more of a work of art than the way he and his students seem to want to take him. The ‘circularity’ of his philosophy and the apparent wholeness, completeness, of his System are apparent to me. It almost seems ‘fractal’ like to me and so, embodies a kind of organic naturalism to it. So, just because I have problems taking him in the way I think he wants us to take him, I can still appreciate his work and the challenge it presents.

The reason I brought up Kant is because Hegel himself brings up Kant as important to his philosophy and therefore, find it relevant to the discussion. It is not based on what I think or others but what Hegel thinks relative to Kant.

With regard to onto-theology I also share a bit of a reservation with the free use of that critique. Neither Hegel or Heidegger ‘should’ be simply reduced to onto-theology…almost as if it were some kind of psychologism of the thinkers. Both thinkers borrow terms from the history of Christian theology but generally have very different reasons for doing so. I have never ever read a word that Heidegger was Christian (hard to see) but Hegel certainly was – does not necessarily mean too much. That being said, there certainly is a theological school of Hegel (mainly Catholic I think) and his fascination with the kenosis and Jesus as, how shall I say, presently the most complete manifestation of Geist does bring him in proximity to a reification of Christianity. Sure, it can have a very different foundational reason but it is curious shall we say. I understand the God/Man dialectic and the introspective subjectivity/individuality he thinks this brings to Geist and history.

Hegel himself in his early writing did employ the aether (Jena I, II, III – unpublished see http://www.cosmosandhistory.org/index.php/journal/article/viewFile/393/781) so it was not just Newton (and others including Einstein) although he seems to have recanted that in his later writings. With regard to the ‘absolute’ in both, I agree that it means very different things but it is not simply ingenious that we observe they both employ the terms. Both were highly concerned with the ‘absolute’. I have read your own comments, something to the effect that modernity has disregarded and lost the concern for the absolute. Both Newton and Hegel were immediately and evidently active about the business of thinking what the absolute could be. An obsession with the absolute has dominate strains in history and while the particulars are different, the direction of the inquiry is motivated by what simply and at least pragmatically is given by the word ‘absolute’. Certainly, what we currently understand by relativity (in physics at least) has deflated that concern and spilled over into contemporary philosophy as you seem to have observed. Additionally, there was crossover from Newton to philosophy and Hegel to physics as temporal/spatial (certainly from the ancient Greek meaning of phusis to physis to Latin nature, etc.). Certainly, there is a passion an intense concern culminating in a lifetime of substantial work after the absolute. From an existentialism and 20th century phenomenological perspective (existing subject, egoistic) they share that desire. It is certainly possible to say they share the same passion without implying that their field of work was the same.

With regard to Being and nothing as immediacy (“pure immediacy”), ‘immediacy’ for Hegel seems to me to be an artificially asserted state (or experience) which, in lived experience, never happens. By the very presumption of ‘immediacy’ as some kind of vegetative human state of consciousness where there is no determinacy (except when it becomes) may be some kind of extremified state of Buddhist consciousness but it can only really be extrapolated as ‘real’ in some sense since, to have it as an experience, would be to lose it in any definitive modality. When we correlate Being immediacy to the nothing immediacy, it seems to me that we have tread into deep waters which has lost the light of day. Sure, we can imagine that state but to think of it as phenomenological, as a lived experience, seems to me to be self-contradictory. It seems to me that immediacy in Being and nothing at the start of the Logic is as Epicurus wrote: “So death, the most terrifying of ills, is nothing to us, since so long as we exist, death is not with us; but when death comes, then we do not exist. It does not then concern either the living or the dead, since for the former it is not, and the latter are no more.” I guess it could be ‘analogical’ for something or another.

With regard to this,

“However, as someone with some eye towards history, may I say that a Machiavellian prince is certainly something that for all realities of our nice natures does seem to be a great necessity in maintaining a shift from one social world to another. To my mind comes Simon Bolivar, whose liberal kindness and resolute moral idealism unfortunately ended up betraying his own dream and that of the continent he helped liberate… all because he refused to be a dictator in a historical moment where such concentration of power and vision was required to see the project of a new Latin America through. Poor fool. As for Hegel’s totalitarian tendency, well, I think that’s overstating things considering the whole of the project is to see the freedom of individuality flourish, which of course requires the stability of its social totality. Take my point with a grain of salt, however, I don’t speak for Hegel or Hegelians here, it’s so far an opinion based on a singular view of history.”

From the ‘world historical perspective’ Bolivar can be thought as a “Poor fool” but I am not sure that exhausts the subject of validity. I suppose we could say that of Gandhi, Siddhartha Gautama, Jesus, Martin Luther King Jr., etc. but the measurement of the success of failure is not necessarily and exclusively taken in some socio-politico aftermath which may or may not have occurred. It seems to me that all of these folks taken in a purely human way had no idea that, at the time, they were going to have a ‘world historical’ socio-politico-consciousness effect. All, at the time, lived their life as if it were simply ‘a life’. Apart from the mythical connotations they picked up in later history, they themselves were not motivated by delusions of (historical) grandeur. It does bring up the question in view of the diversity of possible lived lives, “How shall we live our life? What choices based on what concerns? …an ethical question based on what? …world historical, illusions of grandeur, humble, empathetic, ethical, narcissistic (like our infamous president), etc.?

Also, individuality certainly is one level of Hegel but not necessarily a privileged level. We know the ‘state” is “sacred” for Hegel. Also, Spirit (or Geist) is epochal and collective -even to the point where the individual seems almost slave-like with regard to the state and the Spirit. Individualism seems more like a stop at the beginning of the way where not all individuals are given some endowment of freedom but hold the possibility for freedom as given by their epoch and their ability to perceive it. For the more primitive they must be ‘mastered’ due to their enslavement and further, the end result of violence seems to be a ‘right’ of the…master race shall we say obliquely at the least (ok, too much but can we say that freedom is taken hold of, created by, the enlightened, the Spirit of the age, the victors?).

From this comment “Indeed, these concepts don’t presuppose other concepts, they are what we conceive normally as closest to pure immediacies” I would remark…

I find these parallelisms you name, Being and Nothing, form and content, appearance and essence, thought and thinking, etc. are interesting, especially thought and thinking. Are these suppose to be analogous in some sense? Perhaps as they share Hegel’s predicates of indeterminate/determinate, mediate/immediate, assertion/negation, diremption “of itself into itself as subjective individuality and itself as indifferent universality”. I assume these hinge on existential-particular/universal? Sure, these words can have meanings which, when pushed, can take on these connotations but there is nothing necessary in that ‘push’. I have already talked about the ‘immediacy’ notion but when these other notions are set up as exclusive oppositions, dialectically opposites and negating each other, they seem to artificially and conveniently lose some of their included middles. For example, form and content – form could be a perception of content and thus existential (as what one sees) but perception as seeing does not have to be an externality, a face, of content… an appearance. From a minimal sense there are many ‘ways’ to see the same ‘content’ depending on how – the mechanism, by which you look. In a banal sense we can look at the content of space as visible light, infrared light, electromagnetic, radio frequency, QM, etc. Is the form accidental to content or essential? This is a philosophical question. The fact is that form is never, phenomenally at least, absolutely separable from content. They could be ‘thought’ as antithetical I suppose, as negating each other, but not necessarily. As a side, Nietzsche said ‘my body does my mind’ as a way to turn conventional thought on its ‘head’ so to speak. It seems an abstraction to me to think these predicates as oppositional and exclusively. Sure they can be thought that way but there are other ways such as the same phenomenon, mutually exclusive and inclusive members, purely formal, phenomenal, noumenal, etc. but to lose all these other denotations in a reductionary pool of oppositions is not somehow self-evident. These terms are never “pure immediacies” that can somehow be stripped of their presumptions except in a purely abstract and oracular fashion. We never experience them as somehow separate and purified of their fields of connotations as some kind of sterilized experience of ‘immediacy’. To insist on this ‘immediacy’ is to presume on our lived experience which grasp heterogenous multiplicities of meanings and inflections in everyday, a priori (in Kant’s terms), understanding of the terms. Contemporary phenomenology does not want to abstract and infer/imply abstractions to the way we encounter language but examine how we live them on horizons/wholes of meaning. I know we can think as Hegel would have us think and assume a pure immediacy that is indeterminate but I think there is nothing necessary about that abstraction and, in that only a human vegetable could experience them as such, it would be impossible to isolate those predications as ‘indeterminate’ and still have any such thing as language.

“Finally, to return to something earlier, on your mention of empirical science, pragmatism, and its concepts (such as indeterminacy), I’m not quite sure what you mean without any determinate (ha) case for you to give. I don’t think it would at all be fair to say that, say, the concept of indeterminacy in QM is what Hegel would be referring to by his concept of indeterminacy.”

This is fair enough. I only find indeterminacy in philosophy as an excess to, what I think, is an assumed absolute determinacy based on ‘logical’ abstractions. I think your reasoning is very clear and honest. I appreciate that. In Hegel’s ‘logic’ it all fits together very well, artistically I would say. I think perhaps it really comes down to a choice. Do we want to think that Hegel and his Logic exhaust, sum up, complete the absolute, the all, without excess or even the possibility of being wrong? If we make that choice then I suppose there is a kind of psychological security for some in that determinacy and certainty (as a pragmatic least anyway). For me, indeterminacy leaves open possibility for the novel, for awe and wonder, for an other which has not entered my determinacies and certainties and that also has some psychological component to my choice as well.

Just to let you know, I had full knee replacement September 10th on one knee and the other replaced December 3rd. This has given me more time to read, think and converse than I would normally have. Generally, my days are filled with working out every day, playing/composing/recording music in my studio, writing software for musicians which I really love, reading/thinking/writing philosophy and family. I have really enjoyed this conversations and look forward to future discussions – I just may be a little longer to respond in the future as I get better. I am sure you also have many engagements as well.

———————————————————————————

Antonio…

Unfortunately I find myself by necessity of external factors, but also by choice, outside the road to the ivory tower. Indeed, I haven’t actually read widely in philosophy, but because I know my bit of Hegel so well people assume quite often that I do. It is not due to lack of interest at all, even the philosophers I am antagonistic towards (Deleuze and Schelling for example) deeply fascinate me, but alas I am a inspirational reader and thinker who finds the spark of thought in a community of those who share in the effort and discuss, and outside of academic life this is almost an impossibility. That I have managed so much with Hegel in so short a time and with relatively so little read is almost entirely due to the luck of having met fellow enthusiasts open to the challenge. Most of what you find on my blog is actually written within time frames when I read with these groups and was caught up in the exercise, most of it really was conceived in the total of one year not of heavy reading, but of simply consciously and (mostly) unconsciously meditating on the short parts I’ve read.

Unfortunately I have been and currently am of ‘modest’ means, that is, scraping by. Often people sigh disappointedly at my financial state because they are impressed with my intellect, but think I use it for the wrong things (that which makes no money). Indeed, I may be more busy in the coming weeks which is often not the case, which is why I so readily answer emails. I’m going to be an entrepreneur (financial services), and while I despise the idea, the potential of it and the need of the money requires that I give up my discomfort and shame for a moment in order to achieve anything of this sort. I intend to succeed despite my usual misgivings about bothering people, I must succeed.

Indeed, Hegel places himself in stronger connection to Kant than to his immediate priors, but as I’ve noticed we must not mistake the nature of the relation to flow from Kant to Hegel, such that Kant will somehow elucidate Hegel from outside because Hegel simply elucidates himself and compares/contrasts himself to others.

On the aether, it seems I overlooked mentioning in the last response that I myself stand by a concept of aether. The concept of aether as such need not be absolute qua reference frame, and the implications of physics itself require it for other reasons of brutely paradoxical and conceptual nature. The nature of inertia, radiation, gravity, light, electromagnetism (fields in general) from within themselves call out to our reason to investigate the medium of their reality. Light, for all that we practically do with it, is in itself unintelligible to us, so is electromagnetism, gravity, and simple things like inertia and relativistic mass, particle/wave duality, etc. A relativistic infinitesimal aether not as a type of matter but as a general concept of what is for us indeterminately determinate matter would, given the material reality of Nature, answer and serve the mediating purpose to make intelligible a lot of these strange relations. Not fully, of course, I’m aware that certain issues are present concerning empirical attempts motivated to answer the issue one way or another, and while some of these experiments are supremely well designed, they rest on assumptions on what this aether would be and the nature of what relations may appear as. Multiple individuals far more capable than ourselves in these matters seem to think the conceptual issue is otherwise and far from unsettled, and it is from my experience these individuals who show the greatest grasp of the conceptual issues compared to the standard theorists.

About the parallels, I call them analogies in the Kantian sense of structural equivalences, i.e. we can talk *about* the dynamic of Being/Nothing with any of those and the exact issues will actually present themselves only with a different veneer. It does have to do with the movement of the Concept, but I don’t talk of it in those terms (mainly because they’re so advanced and I’m not so comfortable with it on that level of concretion). You note that there seems something forced in the abstractions of Being/Nothing, that we don’t necessarily have to think this way or think these thoughts, but I shall put that aside for now and simply say that *existentially* you’re right (Fichte has some beautiful words on the choice of philosophy and the individual, but like him I think that though this choice is telling of the individual it is also telling of what this individual is really committed to, and that there are higher and lower philosophies). I’ve been thinking a lot about this in the last couple of days because of you and someone else (the professor I was responding to in a prior email).

======On The Problem of Immediacy=====

Perhaps some elucidation on immediacy is required to make sense of this issue. Being and Nothing are immediate in that they do not presuppose any relation internal or external to them. Hegel says they are ‘equal only to themselves and not unequal to another,’ that they are indifferent within and without. In a way, this is a ruse, and Hegel knows it. We appeal to equality without difference, to innerness without exteriority, to indeterminacy without determinateness, to form without content, to immediacy without mediation as if such even makes sense.

This is the problem of immediacy as immediate: it can never be what it pretends, it itself never has or will be immediate alone. In common talk we speak of the immediate only as it is in mediation: the immediate is precisely something split and differentiated even if the same. Immediacy is always immediacy in mediation, immediate in relation to. We see an apple immediately, the apple is immediately to the right, it is immediately one, it is immediately in contact, it is immediately itself—here A=A, as Fichte shows in his opening to the Science of Knowledge, is itself hopelessly mediated in this posited identity which splits a thing from itself and rejoins it.

Being is absolutely immediate thought. There is not only no thought before or behind it, there is none within it. It’s not a thought at all, it is the absence of it. How did we ever manage to conceive indeterminacy at all? Because we implicitly operated with its opposite, determinacy, in order to determine it so. It is against determinacy’s absence that Nothing is determined. It is by the presence of the very determination of indeterminacy that Nothing is. The implicitness of this, and this is crucial and a very important difference, is in action and not in conceptual explicitness. I’ll explain this further below with thought/thinking.

The dialectic of Being and Nothing entails all dialectics of the Logic. Nothing is. Indeterminacy is a determinateness. Absence is present. Difference is identity. Content is form. Appearance is Essence. Thinking is thought. Subject is substance. Change is permanent. This occurs endlessly because thought and thinking are two sides of one coin which when we attempt to explicitly split will either end in Nothing or it will end in its immanent opposite side of the coin if we simply follow it through for itself.

What is Being? Nothing. It could not be otherwise. What is Nothing? It is indeterminate Being. This is where the action is implicitly happening. Nothing is determinacy (existent thought) falling into indeterminatess because of its drive to absolutize a determinacy we call immediacy, to achieve abstract absolute negation, to remove from content its form, to remove substance from subjectivity — in short, to rip thought from thinking and posit them as utterly distinct. Are we, then, wrong about Being? Is it not the most general, the most universal, the most immediate? Hegel seems to say quite early that, yes, we are indeed wrong about Being. If, indeed, all is, then Being entails far more than itself, but Being as a term has connotations that are more fit for the beginning of this impossible absolute one-sided abstraction.

The Identity

Being and Nothing are one and the same, not by a comparison of their immediacy and indeterminacy, but by the intellectual experience of their reflexive engagement in which one thought supplants the other. Being and Nothing are indistinguishable, they are one and the same concept in this indifference, nonetheless, they are different. They are indeed two different moments of thought, two indeterminacies which have yet to be determinate as thoughts, but we cannot yet immanently specify what this difference is from within the content of these thoughts themselves. We can, however, give an external account for the sake of methodological guidance and explanation. The usual manner of explaining this difference is in the shift of attention between form and content, but I shall opt for a more intuitive (in the experiential sense) distinction.

Thought and Thinking

We must come to awareness and keep in mind the peculiarity of our situation in the Logic: We are existentially beginning at a point far beyond where the Logic begins. We are by the fact of what we are, self-conscious thinkers, capable in ways these lower elements of the investigation themselves explicitly are not. This is also a truth we find in the Phenomenology of Spirit, where likewise we operate with capacities which lower forms of consciousness are simply not equipped to ever conceive or perhaps even come to awareness. Therefore, a key question implicit in this beginning, how we go from indeterminacy to determinacy, will be answered by an existentially determinate capacity — we are not limited to indeterminacy in action even if explicitly we do not call upon it. The capacity of thought is already a determinate capacity, and its power to conceive will be necessarily in use. This power at its most basic can be termed absolute negativity, the capacity to abstract without limit which by implication of its absoluteness determines it as self-operating in that thinking can think of itself.

We can perfectly explain how we arrive at Being is Nothing without making any unwarranted explicit leaps in the thought process by simply using the full capacities of thinking as such in its implicit functions. We must remember: at the outset we do not even know what thought or thinking as such are, let alone how they should function. The only way to find out is to carry out the task of thinking in its purity, and being that we presuppose nothing the only thing to do is to let thought think with the stricture of its self-abstraction. Thinking, being determinate, will operate determinately and determiningly without need of our awareness or comprehension of it.

We can discard with Being and Nothing and just as well speak of Thought and Thinking and still retain the problem at hand: there is a difference that immanently is no difference between thought and thinking, immediately they are recollected in immediacy, but we know that both are true because we know one is the immediacy of observation and the other of action. The indifference lies in that each concept simply falls into the other immediately, and this we find fully intelligible in that we do it in simply thinking these thoughts. However, we are struck by not knowing the intelligibility of the immediate difference within or between each despite the fact that we do make a difference. The difference is an inescapable practical reversal in the movement of absolute cognition exhausting all of its practical capacities: it can engage and it can stand back. Being appears to that which stands back (thought), Nothing to that which steps in (thinking). As noted, thinking already works determinately, so despite the intent of absolute immediacy it is already mediated, and despite the intent of indeterminacy, it is already determinate as indeterminate. The issue, to repeat, about the confusion of the beginning is precisely that the whole operation of thought works implicitly in determinate distinction such that Being is treated as existence (determinacy), Nothing as its absence (indeterminacy), but we cannot explicitly recognize this at the beginning.

This is the ruse, a ruse which after thinking through (never did I think it so much) now appears as not a ruse on us by Hegel, but by ourselves. The beginning works as the indeterminate coming to be determinate only explicitly, determinateness was always already there implicitly, and as Hegel repeats endlessly, we can only bring to explicit light that which is already there implicitly in action. Therefore, you are right of being a skeptic of the indeterminate and immediate beginning, the presuppositionless beginning. I return to my original point: Hegel is indeed presuppositionless explicitly, but the absolute has always aready been there in the process and it is we who are the fools to think we can get rid of its action even if we blind ourselves to preconception. Indeed, the think the indeterminate is not possible for the indeterminate as such, just as in the Phenomenology no form of consciousness can transcend itself if it does not already posses in its power absolute knowing.

==========Individual vs State=========

I feel that I understand your worries of totality and the importance of the Other. Unfortunately, I think it’s a bit of a romanticizing which given your political leaning is not unexpected to find in your theory.

On the individual vs totality, I think the fear here comes from two spooky considerations: the state and the Universal. The state is sacred to Hegel just as Spirit is sacred, and the Universal is sacred—sacred because they are quite literally holy as whole. The state is, for Hegel, the reality of an explicit community open before itself in its own universality. Prior to the life of a state there is a community, there is a Spirit, and the state is there implicitly already. All communities have norms, have rules, have an ethical life which, even if not codified in explicit statements open to the view of all, is nonetheless most definitely there in the very actions of that community’s members toward each other. Since the state is this unity of an entire way of life, the state as community is the basis which generates individuals and is regenerated by them, were we to negate the state and literally dissolve society, the obvious meaning of this is that we will have dissolved our own individuality and destroyed our own Spirit as community. The very ground of the human, its society, is taken from under them and they revert back to a simple animal (e.g. feral children). As a communist you should explicitly value this. Perhaps Hegel may be criticized for speaking of this from the view of some particular state, but according to his own logic the real crime here is for the fall of a type of state in which a higher culture and Spirit will be lost to the seas of history in a dark age, and thus the individual too will regress in that lower society to something less than what had been achieved prior. We cheer for the revolution which advances freedom’s reality, not for the one that regresses us to barbaric times and ideas.

=====On Barbarism in History==========

Of course, your mention of imperialism and conquest, genocide even, of other peoples is certainly a concern. It takes a most cold and purposefully disinterested view of history to claim much of what Hegel claims… and yet even when I considered myself mostly a Marxist I think things become apparent about certain realities which do not necessarily justify the horrors of reality in a moral sense, but explain it in an intelligible sense. When Marx says that all that is solid melts into air, and that capitalism’s historical mission was to reshape the entire globe in its image according to its own logic, the logic which ingrains itself to a peculiar culture and to a peculiar individual that enacts its self-expansion, was this not a mere poetic prophecy, but a prosaic statement of the being of this very power above us in history? Is not capital necessary for the material advancement of life? It seems it is, regardless of private or state capital. The enslavement of humanity to this moment of need is unfortunate, the existent horror something most cannot even look at, the unhinged logic of an abstract universality concentrated in deranged individuals serving but this abstract principle, and yet is this not the reality of history on the grand scale regardless of how we look at it? Is conquest not a progress? Certainly not for those individuals afflicted, but what of humanity? I am from Honduras, a state in ruins. First it was the natives conquering each other, then it was the Spaniards, then it was the US, now it is in addition a war of state vs gangs, etc. Should I grieve for a past people I feel and know no connection to, whose culture even if preserved is not really a culture that lives now? Should I reject the Americans, the Germans, the West in general, for having brought to being some of the greatest luminaries of humanity in the midst of a rape of the world and my people? I can certainly hate them for my life predicament in many ways, but that the West has a way of life and ideals which I would die for is unquestionable. Freedom is not something I will give up, those cultures be damned. Now, I think that if we were fully recognitive in explicitude we couldn’t do what we do to others regardless of their backwardness, but Hegel’s points about not grieving the disappearance of backwards people is simply a logical truth. Nobody rational grieves for the reality of the old ethical life prior to modernity, only for moments of it which we wish we had.

As for the bloody march of history, isn’t it an expected logical conclusion that when this material power is mixed with grandiose or base ambition that all society shakes and trembles under such a boot? And is not such a base ambition born not just of character but of ideal? Does it not, then, come to pass that of historical necessity this is the exact reality: that conquerors found states and institutions, that states unify and homogenize their people, that in the Spirit of the founding is the Spirit of the people, and that these states immanently live and die in the logic of their own contradiction? Should it then surprise us that this mix is not just possible, but actual? That individuals concretize an entire mass of will under their command and as one lead nations to war when interest and ideals collide? Is war not the ultimate sensuous reality of the logic of the other, not as unknown, but as opposed absolutely? To die for an ideal is to die in service of an absolute for us of which no denial or relinquishing is possible. While the boots on the ground may buy a story about an absolute of freedom, the pens in the office tell a story about the absolute of capital. Of course, the winner is not just the one willing to die for ideal, but with the means to kill and survive the opponent.

Ah, but what of those who weren’t founded by conquest? What of those like the Iroquois who seem to finally have recognized each other and come together? They certainly exist, but existence itself is historically of no virtue. The world spirits are those that lead, and we are being led by a train heading towards a cliff—alas, the strong in ethic, will, and charisma are not yet in our camp as champions. —By the way, Simon Bolivar certainly did not see himself as living any common life. He was from nobility and schooled by a radical who veered close to anarchism in many ways. It is this teacher which put him on the path of the vision not just to free Latin America, but with a resolute purpose to found a nation that would rival the United States and not be bullied by external powers. The man had the charisma of Napoleon and the heart of Robespierre, but the aim of a state with the spoken ideals of the US.

As some see it, we humans are adolescents coming to grips with the consequences of mistaking freedom. Who is there, what is there, that could teach us but our own wretched experience? An experience where we have committed and commit collective monstrosities under the guise that something else requires us to do it, under the false pretenses of individuals who care nothing for others and only for themselves. How is this other ever to be recognized without the turn toward ourselves, a turn in which you and I know as individuals partaking in elucidating ideas we have a part, but are hardly the determining part unless we happen to spark an unseen gas. The problems of society aren’t solved with individual reflections, but a whole social movement, and as Hegel and Marx note, history up to now has been a tail that has wagged the dog. The shift to what succeeds capital without stepping back on freedom requires something new and immensely difficult, the self-reflection of a society which understands its position, problem, and determines consciously to meld the solution to the crumbling house in the walls and beams of society itself, in its institutions, in the message of purpose it presents for and to itself.

=====Otherness and recognition=======

There is someone whose works I like despite deep disagreement with their interpretation of Hegel, that is Jay Bernstein. In one of his lectures on recognition he brings up part of this bit about the other. In one it is a point about ‘misrecognition’ which is a popular notion these days, and how American black slaves were and are, according to some, ‘misrecognized’ as an other. Along with Bernstein, I say that’s bullshit. The way we treat these Others is not in fact how one really treats a genuine Other presence. We don’t misrecognize people, it’s not their otherness, it’s the reflection of the negativity we hide in ourselves and which we project onto them. We tell ourselves lies in order that we don’t have to recognize any positivity in them, to hide from ourselves the reality of our own atrocities. Misrecognition on a grand systematic scale is done on purpose, and on the personal case it is done also by purpose hidden in an upbringing which dehumanizes a target.

Were we to meet a genuine Other, and this is just my own musing by the way (conceptually and in example), we’d be talking about meeting a being(s) who exceed our own capacities. A being to whom reason is not limited to our forms, to whom sense is not limited to our forms, and with whom as such we can pretend to have no possible way to truly communicate in a universal discourse of any kind with regard to that which is beyond us and which subsumes us. Of course, to us this being is truly an Other, unthinkable, inconceivable no matter how we play about conceiving it and interacting with it. It would be a being that baffles us in action and in spirit. It would, to use the tantalizing term, really be alien. Certainly the proper life instinct towards the genuine Other is cautious fear precisely in its unknown reality. The other is of course cautious curiosity in attempting to know it.

=========Indeterminacy As Excess========

On indeterminacy as excess against determinacy, the analogy is perfectly right. But now here you fall into a trap: you mistake epistemic indeterminacy for ontological indeterminacy. Phenomenally I’m perfectly comfortable, more than the average person, that reality is more than what appears to us so immediately. But that things do not immediately appear at all is not to say that they are not there, and therefore are already not determinate in their reality. The excess is inconsequential to the Absolute, since it is fundamentally about the total self-determination of thought. On the real philosophy side as opposed to the purely theoretical side of the Logic, Hegel himself is entirely open, especially with the Philosophy of Nature, that the relations and orders of Nature can and will be revealed as not being what we think on the theoretical side. This is why his use of just about everything is in fact provisional. As he cheekily notes, to paraphrase: Even if we were wrong about the empirical determinations that correlate with the concepts we generate, the concepts themselves are true. Perhaps he is wrong that the concept of time corresponds to the empirical reality we call time, but the movement of thought which occurs as the concept of time is for itself true and we should call it something else if need be. So, we can be wrong. We can be wrong about the empirical relation, we can be wrong about how many mediating steps there are in what we wish to talk about, we can be wrong about a lot of things. What we can’t be wrong about is how these thoughts immanently relate to each other.

So, could there be other modes of as of yet unknown sensibility? Absolutely. Do we have any reason to posit such and could we know what they are without any experience of it from ourselves or someone else who can communicate something about it? No. This indeterminate excess, this genuine other, is for us only a nothing, an indeterminacy brought to attention. And note that excess is in relation to us, the mere possibility which can only intelligibly be grounded on our actuality. It is entirely a subjective fancy to dream up that there is the undreamable, just as Lovecraft crafted his horrors in negations and the fear of the inscrutable unknown which is utterly indifferent to us as dirt is to our shoes.

me…

I wanted to respond to the post on love which you published here – https://epochemagazine.org/better-to-have-loved-lost-recognition-love-and-self-211a3948f281. I find the observations you make about love as the result of practical wisdom. Personally, I would not lay the Hegelian grid over the very important and mature lessons one needs to learn to have a successful older age, an in my opinion a successful life. Many never learn these lessons: recognition, desire, abstract and concrete love, self-love (and self-esteem), love for the other (I would also include Other – more on that later) and the ‘better to have loved than never to have loved at all’ which to me translates to ‘to be or not to be– that is not the question – the question is what shall we make of the Other’. I understand perfectly how negation can apply in all the cases you cited. ‘Negation’ in these cases meaning notions similar to what I might think as projection, need, sensual pleasure, recognition by the other which always fails, etc..

However, where I think these dialectics fail is a case you did not mention – what the ancient Greeks had the unique word for – agápe. Agápe is unconditional love like the love a parent has for a child. All the ‘negations’ or pitfalls along the way that you mention can derail a person such that are incapable of agápe when they have children. In turn, this dysfunctionality can result in children that have barriers set up to their mature and full development in the ways of love. Of course, Freud and Lacan both deal with these psychological pitfalls but I prefer Lacan to Freud.